Kennedy (Red Bard): First of all, what an honor it is to be speaking with someone who’s been referred to as, “the Godfather of American anime fandom.” For readers who might not be familiar with you or your work, can you explain who you are and why you’ve been called this?

Robert Fenelon: I’m Robert Fenelon, and why am I called that? Well, Trish Ledoux tried to dump that moniker on me when she was the editor of Animerica magazine. And Helen McCarthy in England with Anime UK refers to me as the godfather of Anime UK. I think it’s… As I wrote in my letter to the editor to Trish Ledoux at the time, it’s like, yeah, that’s too big a title for one person. There’s a whole bunch of people who deserve to share in that title, like the people who bring their VCRs to conventions, hook them up to televisions, open their rooms up and show anime to anyone who wandered in; the early cosplayers, the people who wrote fanzines, the C/FO, Cartoon Fantasy Organization founders, Mark Merlino and Fred Patten started the first anime club in America.

And a gentleman from Philadelphia, Bill Thomas, went out to California, met them and opened up the first branch of the C/FO in Philadelphia. Bill Thomas was this amazing giant of a man who was super friendly and would always talk to newbies and do everything he could to make them comfortable and teach them about anime. This is back in a day and age when there were a lot of gatekeepers running around who like, oh I’m going to protect my sources and I’m not going to tell you what I know. Fortunately, we outgrew that long ago.

But let’s see. I went to one convention, one science fiction convention. The third science fiction convention I went to, I met some people who were showing anime out of their room. They gave me a videotape. I couldn’t watch it. I didn’t own a VCR. To give a small example, I paid $17.50 for my first blank videotape. VCRs were generally between one and $2,000. In today’s money, that tape was about $60 worth, and the VCRs would be up around four or $5,000. And y’know, back then, minimum wage was a buck and change, so maybe $2. But yeah, I wasn’t going to get a VCR anytime soon. So to watch my anime, I had to bring my growing tape collection to conventions, find somebody who had a VCR and beg them. Can I show some of these tapes on your VCR as part of your room party? That’s how I met Roe Adams, who later on would go on to co-found AnimEigo. He was bringing a VCR to conventions and showing chanbara movies, Lone Wolf and Cub, Zatoichi the Blind Masseur. And in later years, of course, AnimEigo licensed those and distributed them in North America.

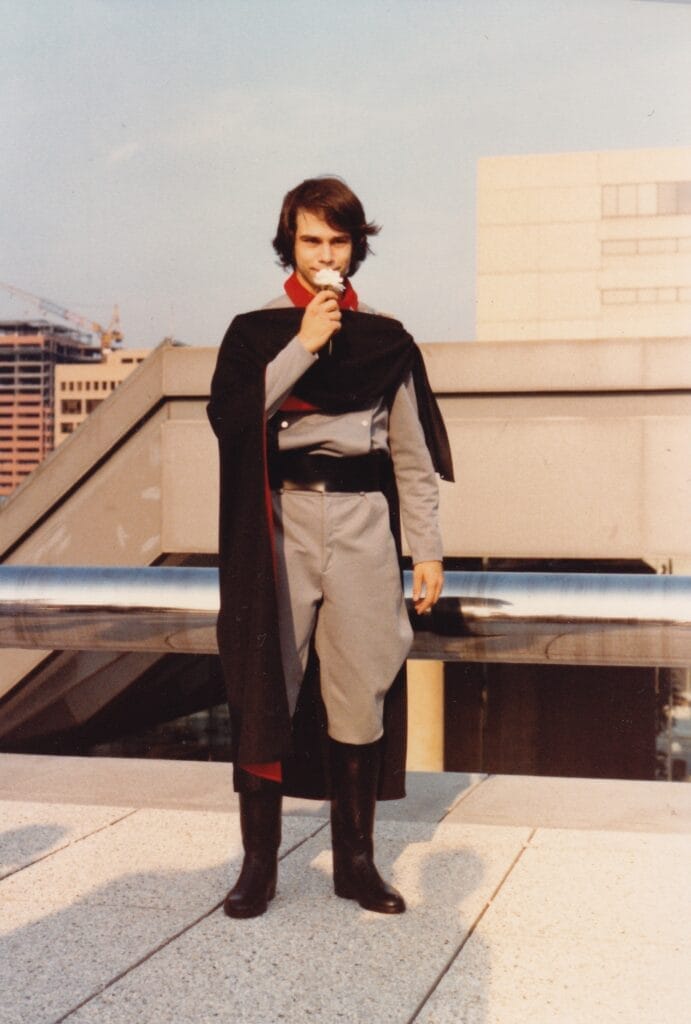

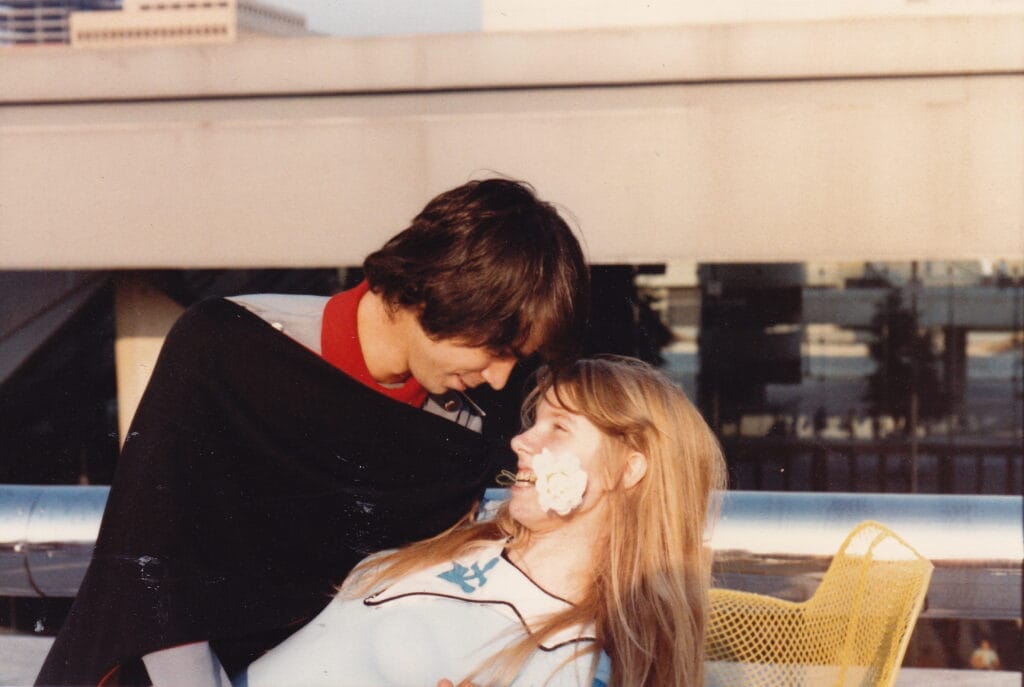

So I was at parties—we call them Gamilon Embassy, because Gamilons are the villains in Star Blazers, and Desslok is my favorite anime character ever. He’s the main villain in Star Blazers. That’s Desler Soto from Uchū Senkan Yamato. And I eventually got a costume made of that character and went around to conventions doing the hall costume thing. Then in AnimeCon 91, I got up on stage and did a little comedy routine based on an old Bill Mimbu comic about the Gamilon Express Guard. It’s on YouTube. Just type in “Robert Fenelon” and you’ll see the video of my little performance.

So I was a cosplayer. I was an active fan who was showing video to people. Later on, I worked with Lunacon science fiction convention, and we ran a Star Blazers room there, which is what they used to call anime video rooms back when. But it rapidly changed to the anime room, and we would show a variety of movies and selected episodes. I would occasionally cut together a compiler out of an entire season of a TV show and run that. This is before fan subtitling. So someone who thought they knew what was going on—which was usually me—would stand up in front of the audience and explain what they thought was happening while it was happening on the video. And so we had narrators. And years later, C. Sue Shambaugh ended up translating a whole bunch of scripts to movies and typing them up and releasing them into the wild. And people would be passing around photocopies of these. And so we finally got to know what was really going on in some of these movies.

I got involved in the Star Blazers Fan Club. I saw one of their flyers and sent in the money to join. Their latest issue of their little photocopied newsletter, the Star Blazers Fandom Report, said that they were going to be at a Creation Convention show in August. Creation was an old for-profit science fiction convention. It was basically little more than a dealer’s room in an autograph session. It was a for-profit organization. They had Creations up and down the East coast at least once a year in each major city. I showed up and met the Star Blazers Fan Club people. They had been given 200 seats and a TV and a VCR in one corner of the convention center. The problem is they were watching the recent Flash Gordon cartoon and the dealers were stealing all their chairs. So my introduction to the Star Blazers Fan Club—or I should say their introduction to me—was this bossy guy who came around and dragged a few of them out. We went to table after table and took back the chairs that the dealers had stolen so the audience would have some place to sit.

I had sent them a letter when I found out they were doing it, said, “Hey, if you don’t have anyone to narrate Arrivederci Yamato, that’s like, my favorite to narrate.” And they said, “We don’t have any narrators at all.” So I spent a lot of the time in front of the audience narrating. Fortunately, my grandparents were politicians and my parents were industrialists, so I’d been trained from a very young age to do public speaking. I’d been in a school play every year from kindergarten on. So I’m really good at projecting my voice and not getting a sore throat because this is the days before they’d give you a microphone. I only got a microphone briefly and that was to make an announcement to the entire convention. And I said, “Yeah, coming up at such and such a time is the movie, Arrivederci Yamato! It’s the sequel! It’s the second season of Star Blazers, except Desslok dies! Wildstar dies! Nova dies! EVERYBODY DIES!” There was standing room only for that.

One of the people we drove home on our way back to Boston, one of the people who had an apartment in the building I was in, Steven Carey, had a Hearse, a 1969 Miller-Meteor, like the biggest Hearse you could imagine. And so we could fit a lot of people in it and drive them around. And he had a bed in the back, so people be relatively comfortable. And we dropped Christopher Claremont off at his apartment in Northern Manhattan, Southern Bronx—it’s hard to tell where one ends and the other begins. And I always wondered, because a year or two later, he did an issue of X-Men, where the cover title in three-inch tall streaming type is “EVERYBODY DIES.” And I always wondered if maybe he was perhaps remembering my little carnival barker thing about everybody dying.

Another reason why people might call me a godfather of American anime is there were clubs all over the country that wanted to show anime at conventions. And science fiction conventions were generally hostile to anime. We were the unwanted, redheaded bastard stepchildren of science fiction fandom. A lot of science fiction conventions were in the grasp of people who were old-fashioned. The only science fiction that counts is the authors writing the science fiction. The only thing that’s legitimate at a convention is they meet the pros party where I get to talk to Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke and people like that. And they were hostile towards, “Oh, that media stuff like Star Trek.” So there was a lot of resistance from a lot of conventions when people said, “I want to run an anime program at your convention.” And some of the conventions—science fiction conventions—took the tact of saying, “Well, we’re not going to let you show it unless you get permission from the copyright holder to show it.” Which of course was bogus because these conventions were showing Star Wars and Star Trek movies in their main ballrooms. They didn’t give a damn about copyright.

But fortunately I knew Claude Hill—the man who owned Westchester Film, the company that brought Star Blazers over and had it dubbed into English. And at the time, there was a branch of Toei Animation in California, and I got to know the people there. And I would get letters from two different organizations saying that, “Such and such convention has the permission to screen any titles that we are the copyright holder of.” And that way, if a convention committee—a science fiction convention committee—says, “Well, what are you showing?” “Well, we’re showing Urashimon.” “Well you can’t,” said the concom. “No, it’s one of the Toei shows” was our reply. Which was a lie, as Mirai Keisatsu Urashiman was from Tatsunoko. But what the heck? Someone from a science fiction convention isn’t going to know which anime was produced by which animation studio in Japan. So I helped a lot with that.

I eventually met the Moriarty Brothers. Richard and Gerald Moriarty, sadly, both passed away over the last decade. They were twin brothers from New York City who would go to conventions and bring their VCRs and show anime out of the rooms. And the New York C/FO, for years, it was them dragging their TV and VCR down from the Bronx to Manhattan to show videos there. They’re often called the patron saints of the C/FO. They would trade tapes with anyone. If you didn’t have anything to offer them in trade, they’d pretty much… I think that Richard’s policy was, “Give me three blank VHS tapes and a list of what you want, I’ll put that on two of them and give two of you back and I’ll keep the one in trade.”

But they were like Bill Thomas.They were real sweethearts who would spend the time to talk to newbies and introduce lots of new people to anime. And I met them and they had a huge collection of anime because they had been taping… UHF channel 68 was Spanish in the mornings and the afternoon, but on Saturday evenings it was Japanese. And they were rerunning animation that had been subtitled for Fuji Telecasting in Hawaii.

So they had tapes of the first Sentai show, Go Ranger. They had tapes of Yusha Raideen, one of the oldest, greatest giant robot shows. They had Cyborg 009, my personal favorite of that era of anime—a bunch of international superheroes fighting in an evil court’s conspiracy. They had Ikkyū-san, which was about a Zen Buddhist monk who was always making the shogun look like a dope. Let’s see, Star Prince Chobin, which was kind of like an earlier iteration of Furby. Oh, and Captain Harlock and Galaxy Express 999 and Queen of a Thousand Years. Back then, a lot of the anime that we saw was Leiji Matsumoto animation. And with the Moriarties, I would go with them to conventions, and it would be at least once a month, sometimes twice a month, and we’d be showing stuff to the public and I’d be doing the narration.

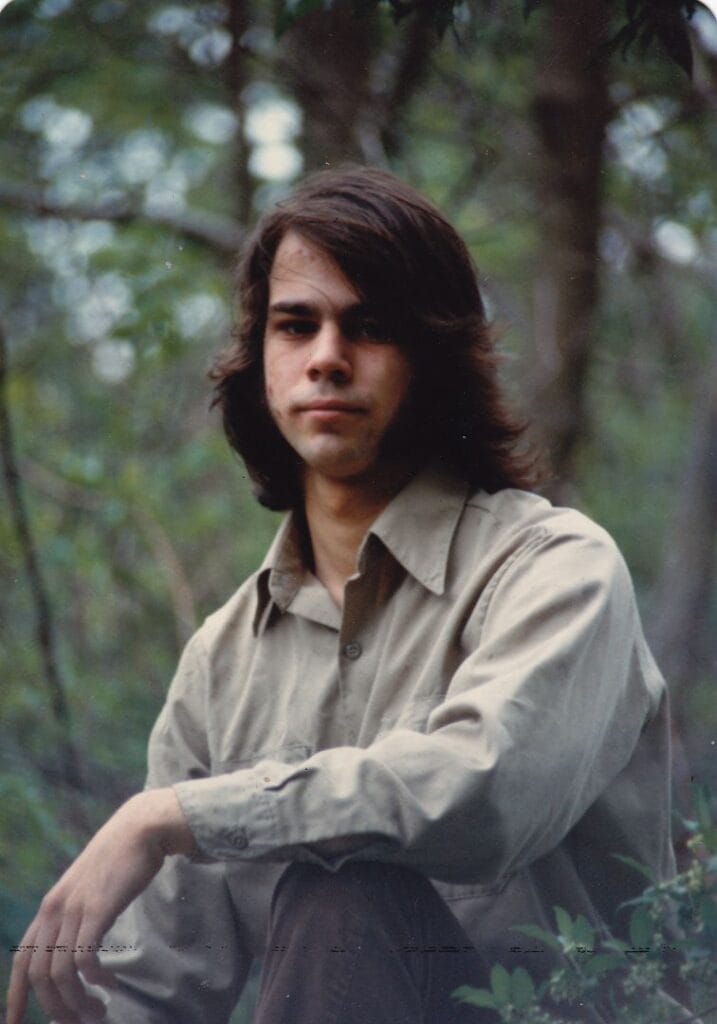

So I was a cosplayer, I was showing animation at conventions, anime conventions, and I was helping other groups around the country overcome the hostility of science fiction conventions. I was an early cosplayer. I had my Desslok costume in 1983, I think, was when I got it. Yeah, because the Worldcon, which I gave you photos of when we had more than a dozen cosplayers on the roof of the convention center, that was the first convention I was showing my costume off at, and we hadn’t gotten the cape to drape right because the way it drapes in the cartoon, gravity doesn’t work that way. Later on, I got a hook and eye snap on one of my shoulders to make it drape the way Desslok’s cape actually drapes. His cape wraps around his right arm. So whenever you are walking forward and swinging your arms, the cape is swirling back and forth. And the one Desslok costume I’d seen before mine, they didn’t figure out how to do it, so he had a bib in front of the cape. But fortunately, Colleen Winters did some sketches to show how it would work in real life, and I gave that to the person who I hired to put the costume together.

So I was an early cosplayer. I was helping people get anime at conventions. I was helping the New York C/FO. I would often make the announcements there and talk to people in front of the audience. That C/FO had been up in the Bronx in someone’s basement. That person was Jerry Beck, who founded the New York C/FO. Jerry Beck would later move to California and meet Carl Macek, and they would found together the company Streamline Productions. So the co-founder of Streamline Productions was the founder of the New York Cartoon Fantasy organization.

I guess these are the reasons why she chose to call me the godfather of anime fandom? I’m sure she had other motivations, but I was an early fan who was talking to people and proselytizing it. It’s like, “This is so cool! You got to check it out!” Part of that was because the only way I could see it was to show it. When I got my very first videotape, I didn’t have a VCR, of course, for years. And up in Boston, they had a club where you could come and pay a monthly fee and use their VCRs. They were Betamax machines, so I couldn’t watch my VHS tape there. And then a friend of mine told me that Massachusetts Institute of Technology had a VCR in their chemical engineering laboratory. So I went there with my tape and bounced off security the first time. Second time, I showed up in a suit and tie and had a clipboard with me because if you’re carrying a clipboard, you’re official. You’d be amazed how many security people I have passed by, by just having a clipboard with me. This is, of course, before 911. And I waved the tape under his nose and said, “Look, I’m bringing this in with me. I’m going to bring it out with me.” Thereby implying that I was totally legit there and had been here before. And found the VCR, put my tape in it, and the VCR would only play in two two-hour speed, and it was a four-hour speed tape. Everyone’s running around in fast motion talking like they’ve been inhaling helium. They’re all high, squeaky voices. But I watched it three times in a row.

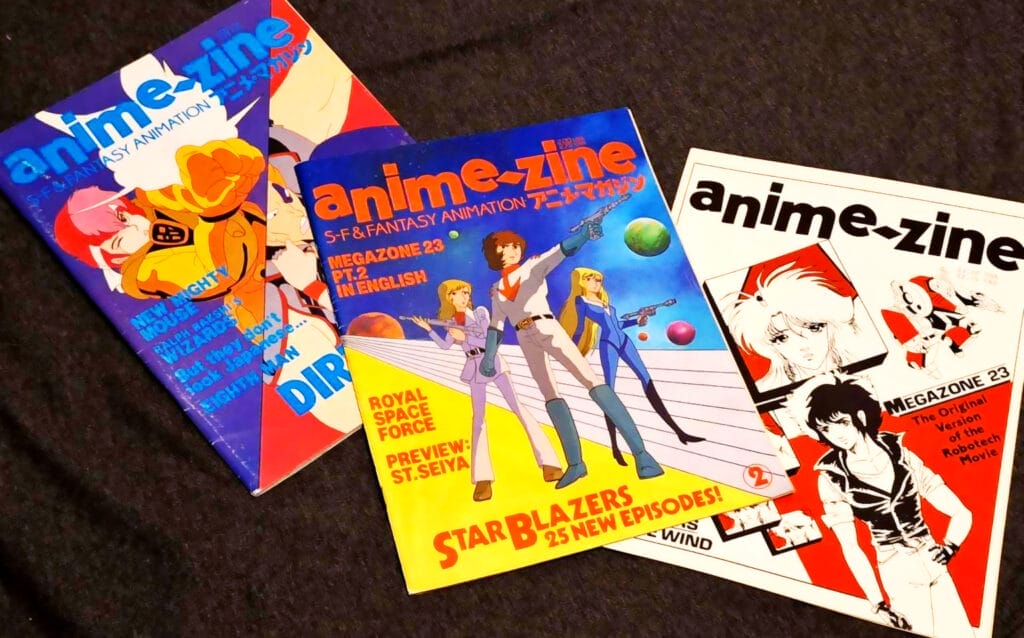

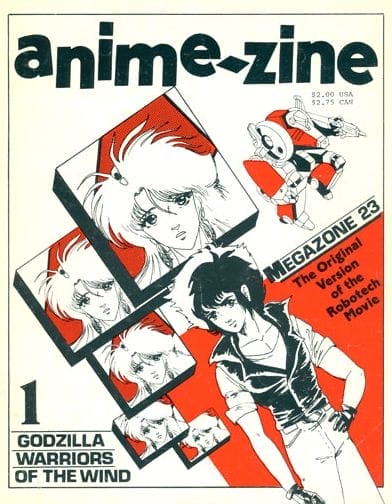

This was a videotape that had been circulating among anime fans back in the early 80s. This was 1981. Back in the early 80s, everybody seemed to have a copy of this tape. It was Yamato New Voyage, three episodes of Mobile Suit Gundam, and the pilot for Ideon. Depending on what generation you had on this, it could be black and white. As the quality goes down, each time you make a copy of a copy of a copy. One of the reasons I love electronic storage of videos is I don’t lose any quality while I’m going down, while I’m making copies. So yeah, there’s your answer to your first question. This is probably why she called me the godfather of anime. Helen McCarthy called me the godfather of Anime UK, her magazine, because she and Steve Kyte, her husband, were inspired to do Anime UK when they saw copies of Anime-Zine.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Now, speaking of Anime-Zine, Anime-Zine‘s roots can be found in Star Blazers fandom, in particular, the Star Blazers Fan Club that you mentioned earlier. What can you tell me about the Star Blazers Fan Club and your involvement with it?

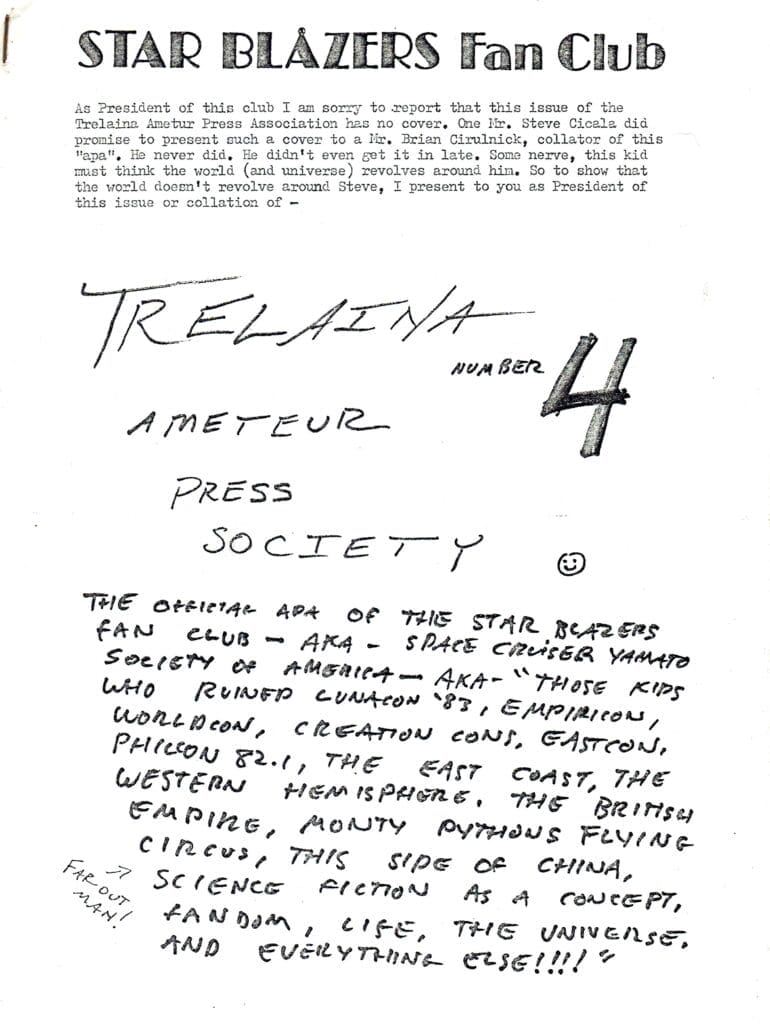

Robert Fenelon: Well, like I said, I met them at a Creation in August of 1981. It was either that or a later Creation convention. I think it was at Creation in 1982. Now, the leader of the club was Michael Pinto. He founded the club. And there were several people who were helping him out. Fred Kopetz was involved in the club, and he founded the first Amateur Press Association dedicated to anime in America. It was called Starsha, named after the benign queen of space from the first Star Blazers series.

An Amateur Press Association is a very slow-motion, low-tech, labor-intensive bulletin board run on paper through the mail. We can get more into that if you’re interested in that later. But another person involved was Brian Cirulnick, who helped out a lot. And there were a few other people, but mostly it was Michael Pinto and Brian Cirulnick and me. And once I came in, I kept pestering Michael Pinto to broaden the magazine, his newsletter, from just Star Blazers to other topics. I got Patricia Malone to write articles on Macross—which hadn’t come over as Robotech yet, it was still Macross. I did an entire issue just on Macross and started getting people to write articles on other anime besides just Star Blazers.

I ended up taking over more and more of the editorial responsibilities of putting together the Star Blazers Fandom Report. Eventually, Michael Pinto was no longer interested in running the club, and he handed the reins to me. He gave me their treasury—which was a whopping $80—and the mechanicals for the last few issues of the Star Blazers Fandom Report. He said, “Here, do whatever you want with this.” What I wanted to do was to do something like Animage magazine in Japan, which was of the various anime magazines printed in Japan that got shipped over to America and sold at outrageous prices over here. It was the most information-heavy and the most text-heavy.

Fortunately, I found a really good graphic designer, Luke Manichelli, down in Pennsylvania, who did the graphic design and was finally able to have complete creative control over how he did it. So it’s very big pictures, and when he arranged a bunch of pictures on a page, he was using Ukiyo-e woodblock print patterns from Tokugawa Shogun propaganda leaflets that were printed on woodblock printing. So interestingly enough, he got this from a magazine called Signal in the library. And Signal was a World War II publication in Germany that had a Japanese graphic designer doing their graphic design. The graphic designer for Anime-Zine was basing his designs on a Japanese person working in Germany in World War II who was basing his designs on 300-year-old propaganda leaflets. So Anime-Zine is very… It’s the revolving door of culture.

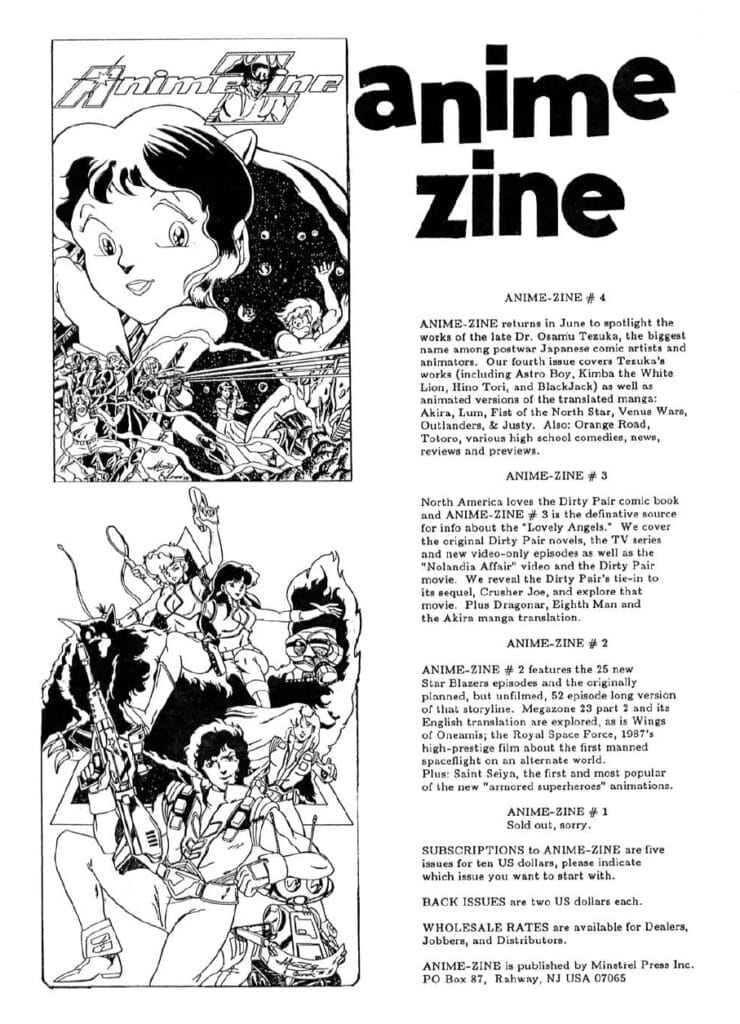

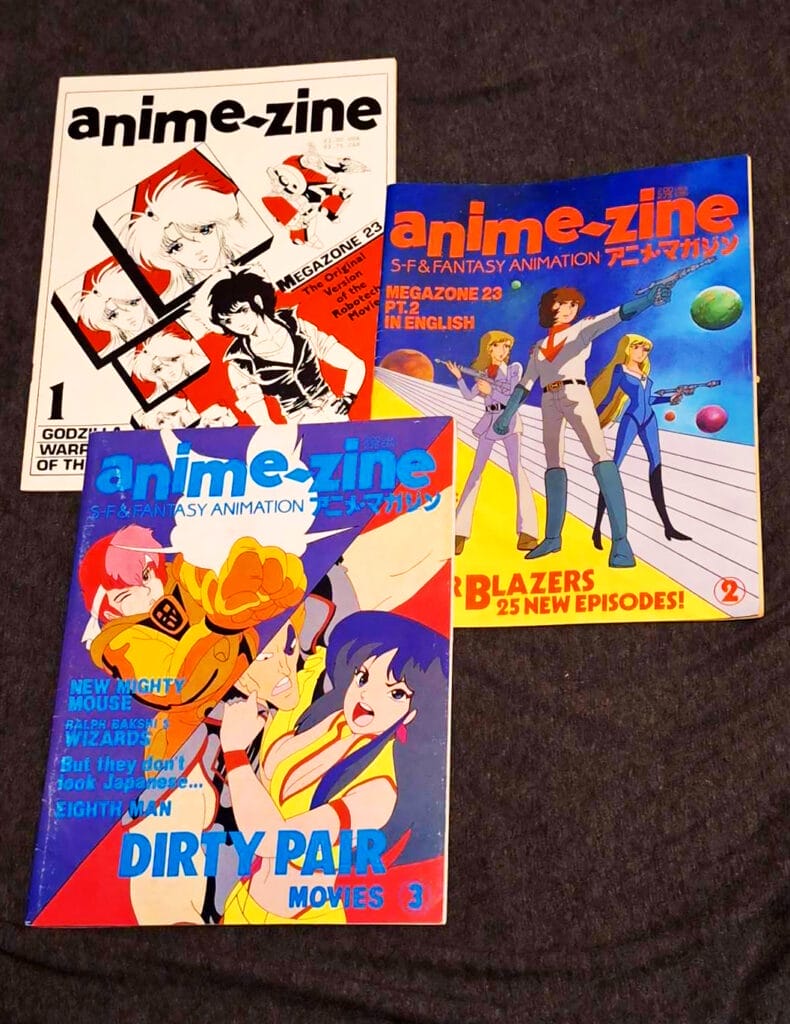

And I wanted to do something bigger and better, and I didn’t want to mail to a mailing list of a couple of hundred people. And I had some contacts in the comic book industry, mostly through Marvel Comics. I knew all about the distribution setup of how comic books from Marvel and DC and the various independents were sold, wholesale. There were a dozen distribution companies at the time—more like fourteen—that would buy from the manufacturers and sell all over. Although by the time I came around, they’d stopped selling to drugstores and supermarkets and were only selling to specialty comic stores and bookstores. I used those contacts to sell Anime-Zine through Diamond Comics and Silver Snail Comics and all the other distributors that existed back then. And we were selling all over English-speaking North America. Silver Snail, for example, was in Canada. So instead of 100 issues of something photocopy, we were actually using a print shop in Southern Manhattan to print up thousands of copies and send them out. I think the first issue was like 6,000 or 8,000, but then we were pretty much 10,000 for the second, and I don’t remember how many for the third.

And that’s how Anime-Zine started. So it was professional and it was distributed countrywide. There were other anime publications before me, of course, like the C/FO National Group had a really good newsletter that was coming out of Florida by Jane E. McGuire, I believe. But basically, they had this info-zine that had articles on Gundam and stuff that would go through the national organization to the people who would pay $10 a year and then would be shared around with other people. And there was a magazine out in Chicago called Japanimation. And that came out before mine but was only distributed in Chicago, and not through the comic shops. Pardon me, it was distributed by them taking it to the comic shops and selling it there on consignment. So I’m pretty sure Anime-Zine was the first one that was professionally distributed around the entire continent. I’ll put in a photo of two of the people who are very important.

In this photo, the person on the right is Pat Malone. She was the president of the New York C/FO who moved it down to Manhattan and let it into its gigantic size. And on my right, on your left, is Beverly Headley. She was an immigrant from Barbados who in later years married Richard Moriarty, who I mentioned earlier. And Beverly was the business person who put together the company that published Anime-Zine. It’s something that I think doesn’t get mentioned enough, but a lot of the movers and shakers of early anime fandom were women. Because we came out of science fiction fandom where there were very few girls. But anime fandom attracted a lot of women, so we had a much higher percentage of women as anime fans. And a lot of the people who were really pushing anime were female. And that’s something that I don’t want historians to ignore.

Kennedy (Red Bard): I’m very glad that you’re making a point of saying that, quite frankly. So thank you for that.

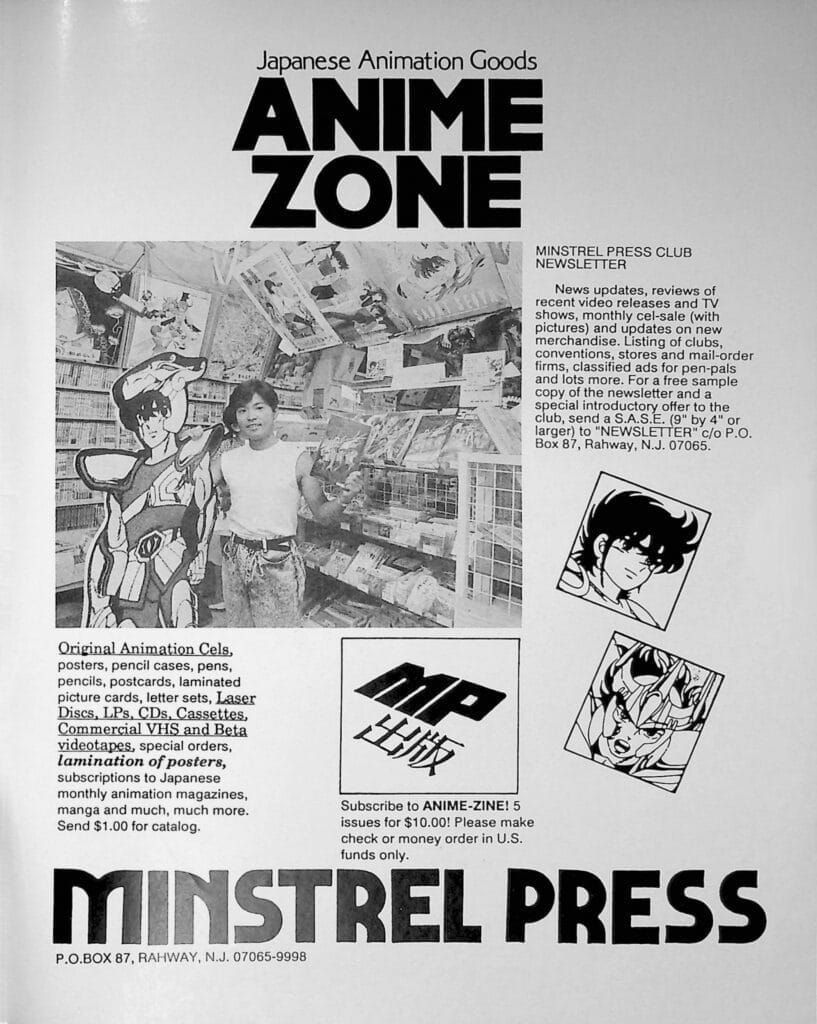

Robert Fenelon: And as Walt Amos pointed out a couple of weeks ago—Walter Amos pointed out that Beverly Headley, or Beverly Headley-Moriarty later, was an early mover and shaker of anime, put together a profitable corporation. We also had a Let’s Buy Stuff Wholesale in Japan merchandise posters, whatever, and sell retail in America that Mary Kennard was running. And I brought in Anime-Zine and Mary Kennard brought in her little import business called Anime-Zone. And Bev put together an umbrella corporation, Minstrel Press, which raised the money to do this.

What Walt Amos pointed out is, look, here’s one of the big wheelers and dealers in early anime fandom. She’s a black female immigrant. So there, to all you conservatives, is what he said. I don’t want to get into politics. But yeah, we did three issues of Anime-Zine. We were selling stuff through Anime-Zone. And Mary Kennard found a job in Japan and moved to Japan and was working for Comic Box, which was technically a fanzine publication, but it was a company run by fans. They were a pro magazine with pro distribution, which in Japan means hundreds of thousands if not millions of units.

I was talking to a friend of mine who was an editor at Marvel Comics, and we were in this weird bar in New York. And he said, “Yeah, our circulation is dropping. The latest X-Men, which is our flagship title, only sold 250,000 copies.” I said, “Well, you know, Shonen Jump, which is the best-selling manga in Japan, sold something like six million copies two months ago.” He fell off his bar stool. They had no idea what it was like in Japan—a country with less than half our population, which produced way more magazines. And it’s cheaper to print in Japan because in America, print shops had geographic monopolies, and they literally would not compete with each other. In Japan, they had a lot more print shops savagely competing with each other and slashing away at each other. The Japanese print shops were always adapting the newest technology and printed pretty cheap. If you go to a Japanese fanzine sale like Comic City or Comic Market or Comiket or whatever, you will find people with fanzines where they’re bringing 10,000, 50,000, 100,000 copies of a fanzine they printed and are selling it for 150, 200 yen—or at least they were back in the 80s when I went to Japan. And that’s like, a buck. You couldn’t print anything for a dollar back in America back then. It would be way more expensive and it wouldn’t have nearly the quality.

So, yeah, print shops were geographic monopoly. And Pat Malone worked for one in New York—not the one we used. But why did I bring up geographic monopoly of print shops? I’ve lost my train of thought.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Totally fine.

Robert Fenelon: Yeah, it was expensive. Like I said, Mary moved to Japan, and then Bev had a stroke and was hospitalized for a year, and a drunk driver broke my neck by hitting my car from behind when I was at a red light. I was completely out of commission for more than a year. So was Bev, and Mary had left the company in Japan. And the company never recovered from that and never became profitable again. And I got the IRS to put it out of its misery and shut it down.

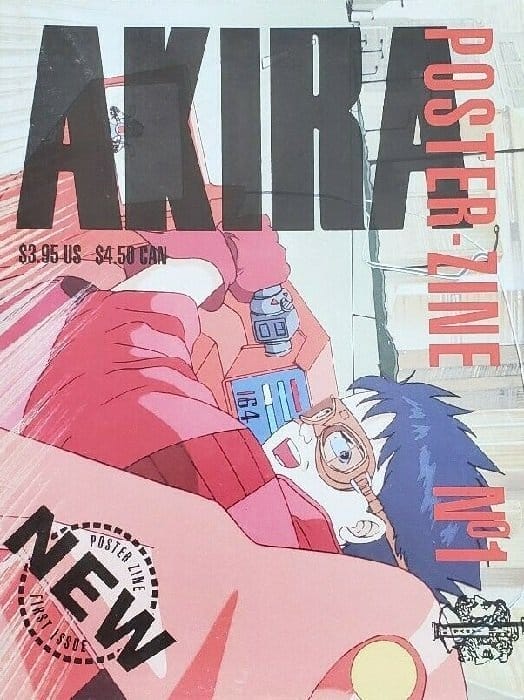

You mentioned Protoculture Addicts earlier. A friend of mine was Claude Pelletier, who was one of the publishers of the Ianus Publications, and they did Protoculture Addicts. And I was helping them out and they were helping me out. And the people who had paid a subscription for Anime-Zine got their subscription fulfilled with issues of Protoculture Addicts when we stopped publishing Anime-Zine, they got the rest of their issues from Protoculture Addicts. And I created a magazine for them called Poster Zine, which would unfold in one side was a full-size movie poster, and the other side would be various different articles.

I wanted to do something recent. They wanted to do Akira. It came out, it was nice, it sold okay. But then there were all kinds of complications because Quebec was considering seceding from Canada. They were going to have a referendum. Claude was a Reservist in the Canadian Air Force. And the federal government of Canada mobilized all of the military assets in Quebec and moved them out of Quebec so that if Quebec separated, they wouldn’t have an army or Navy or Air Force. And the company was suffering because a lot of people at Ianus Publications were Reservists. And the fact that Protoculture Addicts and Mecha Press were making more money than Poster Zine was pretty much what put the kibosh on Poster Zine.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Now, earlier you touched on this, but I want to ask it again just for the sake of clarity. Or if you want to expand on that, you can do that, too. Anime-Zine is frequently referred to as North America’s first anime magazine. Do you think that’s accurate?

Robert Fenelon: No. Anime-Zine was North America’s first professionally distributed anime magazine. There were C/FO newsletters and the C/FO National had a… I’m sure their print room was under 200 copies, but they would send it out to people all over English-speaking North America. You’d get one, you’d share it with your friends and share the information in it. The C/FO magazine had been going for years before I started Anime-Zine. The Star Blazers Fandom Report was a little newsletter that had been running for years before I showed up on the scene. There was this magazine out in Chicago called Japanimation. I refuse to pronounce it the other way—Japanimation, I refuse. They ran at least one issue. I remember they had a Dirty Pair article where they had synopses of eighteen of the twenty-some-odd episodes, and the rest of them were just blank. That’s something I never would have done. But that was a magazine and it got sold in Chicago. Mine was the first one to be sold through the comic book distributors, through professional distribution outlets all over the country.

Kennedy (Red Bard): And where was it sold?

Robert Fenelon: Well, the companies that bought it for me that I wholesale to, would sell through comic shops and through bookstores. There were comic book shops all over the country by this point. The comic book business model had gone from spinners in drugstores and supermarkets selling comic books to just comic book specialty shops. That was a niche market, and I was a niche in that market because Anime-Zine was not comic book-sized, it was magazine-sized. Comic book shops don’t have as much space for magazine-sized as they had for comic-sized, so they had less money to spend on magazines like mine. And I was competing with Fangoria and a few other magazines like that for that limited shelf space. But I saw it in Forbidden Planet in New York. I saw it in a Silver Snail’s flagship store up in Ontario. I saw it in some place out in San Diego. I don’t know the name of the comic shop. But yeah, pretty much all over the country it was sold.

Kennedy (Red Bard): So unbeknownst to you at the time, issue 3 would end up being the last issue of Anime-Zine. And in fact, there was planning underway for volume 4 to the extent that at the start of that third issue, there’s a mention of plans to add a full color spread to issue 4, and that its price is also going to be slightly raised. And there’s also an ad for it in an early issue of Protoculture Addicts. What can you tell me about the plans that were in place for this issue 4?

Robert Fenelon: Well, before we lost all three of our rather limited staff, each issue made more money than the issue before, and each issue was bigger, with room where we were able to add more stuff. I was particularly proud when I got Patricia Malone to write an article on the costuming in Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which was based on costuming from Poland in… I can’t remember which century. So we were trying to put in a lot of different information, and we were going to have the money to do the extra stuff. Full-color cels. There was a debate going on whether we should have a full color center spread or whether we should put it as a page-3 and the second to last page.

I don’t know how that would’ve turned out. At that point, we had one of the people who’d come into the orbit of the Moriarties. And make no mistake, I was not the center of our group—Richard and Gerald Moriarty were the center of our group. Bev and I and a whole bunch of other people were… I was from New Jersey, she was from New York, the Moriarty brothers were from New York, but they were basically the center of this group of people who were all anime fans and war gamers and comic fans and role playing gamers.

Okay, that’s not answering your question. One of the people who came into orbit was Martin King, who was an artist for DC Comics. And Martin had some kinda connection—or at least he claimed to have some kinda connection—with Jack Kirby. And we were trying to get in touch with Go Nagai in Japan. And one of the things that Martin had proposed—and I thought it was genius, and if we could have arranged it, it would have been the center spread of whatever issue we put it in—was a 2-page spread where one side would be Jack Kirby would be penciling the demon Etrigan, one of his characters. And on the other side of the center spread, Go Nagai would be penciling Devilman. And then they would each ink the other’s page. And apparently, Jack Kirby was interested in this. He was really charmed when he found out that Go Nagai was called the Jack Kirby of Japan. Pretty sure that happened before he ever met Martin King. But that was another casualty of what we were doing. It would’ve been great. Unfortunately, Jack Kirby passed away a few years later.

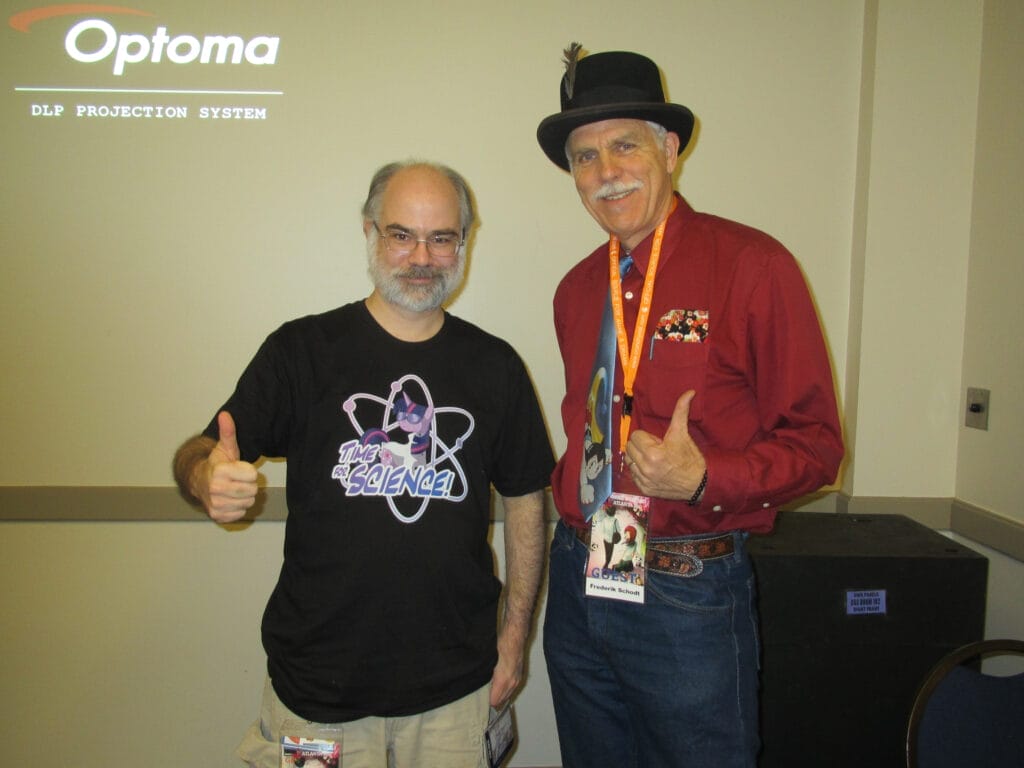

If I could backtrack to professional publications before Anime-Zine, one of the most important was a hardcover coffee table book called Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. That was written by a gentleman by the name of Fred Schodt, who’s an excellent translator and spends a lot of time living in Japan. That came out in 1980 or ’81 before I started doing anything. And it was a fantastic guide to what manga was all about. It had a couple of pages of translated Rose of Versailles in it. I think he coined the term “sports guts.” The most recent photo I put up is me and Fred Schodt in 2013 at the Anime Weekend Atlanta. I think we were on panels. He’s someone I talked to at conventions. I don’t remember whether or not we ever did any panels together. But an extremely friendly gentleman of the old school, very polite, very gracious, cool guy. But yeah, that was really important. I’m sure Manga! Manga! reached far more people and had far more influence than Anime-Zine ever did.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Now, speaking of reaching people, do you remember how many readers you had or how many letters you were getting? Just anything that could quantify what the readership for Anime-Zine was like.

Robert Fenelon: I can’t give you exact figures because unlike the comic books, when magazine-sized publications like my own or like Fangoria or Starlog were sold to comic shops, they were not returnable. In regular comic books, they would return the unsold units or tear off the covers and send back the covers. So a comic book publisher knows exactly how many copies of each issue sold. All I know is that we would sell a certain number of them and we were paid up front by the comic book distributors. Then they would sell them to comic shops and if the comic book shops didn’t sell them, that information never got back to me. So I don’t know accurate numbers.

All I can tell you is that for the first issue, it was… I wish I remembered this. It’s something like 6,000 or 8,000 copies. The second issue was 10,000 copies, print run. And I would keep one box back when we sold the rest. One box… Oh God, how many were there? At least 150 copies I would keep back, maybe more. And those would be sent out to reviewers, to other publications for them to write about, to review, to as freebies and samples to people who might be interested.

I’d occasionally get a comic book shop contact us directly asking to buy directly instead of going through the middleman. I’d send them a copy of the latest issue and say, “Well, here’s what it looks like. Here’s what we’ll charge you. And here’s the shipping and handling, depending on how many units you order.” So all I can say is we printed 10,000 copies of the second issue and more of the third. I wish I knew. I wish I remembered how many copies. And most of them sold, at least on the wholesale basis. I have no idea if any of them ended up on comic book shelves being unsold.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Going back to that would-be issue 4, do you have any images, articles, or anything else from that would-be volume 4 that you could share? Totally fine if you don’t.

Robert Fenelon: I don’t have anything from any of the issues. I don’t have the mechanicals, because unfortunately, flood. My apartment was in the basement and we had some bad noreasters and a lot of my most important possessions were destroyed. And I’ve moved twice since then. I have in storage in a shed out back behind this building, there are a bunch of boxes that I haven’t opened since I moved into this house in 2002. So it’s possible I may have some of that information there.

If I can brag about Anime-Zine a little, there’s a lot of stuff I’m really proud of. Like the type of articles we got. Lynn Morton and Martin King did some translation of the third season of Yamato. And I’m aware of Yamato 3 because back in 1981 when I lived in Boston, I was getting a magazine called The Anime? Yeah, there was My Anime, The Anime, Animage, and Animedia. But The Anime was running a photo novelization of the third season of Yamato. Each issue would have several several-page-long photo novels of that issue using stills from that episode of Yamato 3.

And I was aware that it was fairly low budget. It was the first co-production between Japanese and Korean studios. Yoshinobu Nishizaki, the creator and producer of Yamato, created South Korea’s first animation studio—or at least the first animation studio that ever did work with Japanese companies. At one point, Nishizaki told me that they didn’t even have blue pencils. He had to have them manufactured in the United States and shipped to Korea. You need blue pencils when you’re doing the douga—the paper sketch that goes underneath the animation, the painted cel. And I knew there was more out there.

Now, the first season of Yamato had originally been going 52 episodes. It was canceled, and around episode 24, they were told, “You only have two more episodes.” So they drew it to a rapid close. They were up against Heidi of the Mountains, which was on World Masterpiece Theater, and it was a juggernaut in the ratings. And Yamato, even if it was the first science fiction series in Japan and even if it was super popular with teenagers, it was buried in the ratings by younger people watching Heidi. And I suspected the same thing happened in the third season, and yes, it did—it was originally going to be 52 episodes.

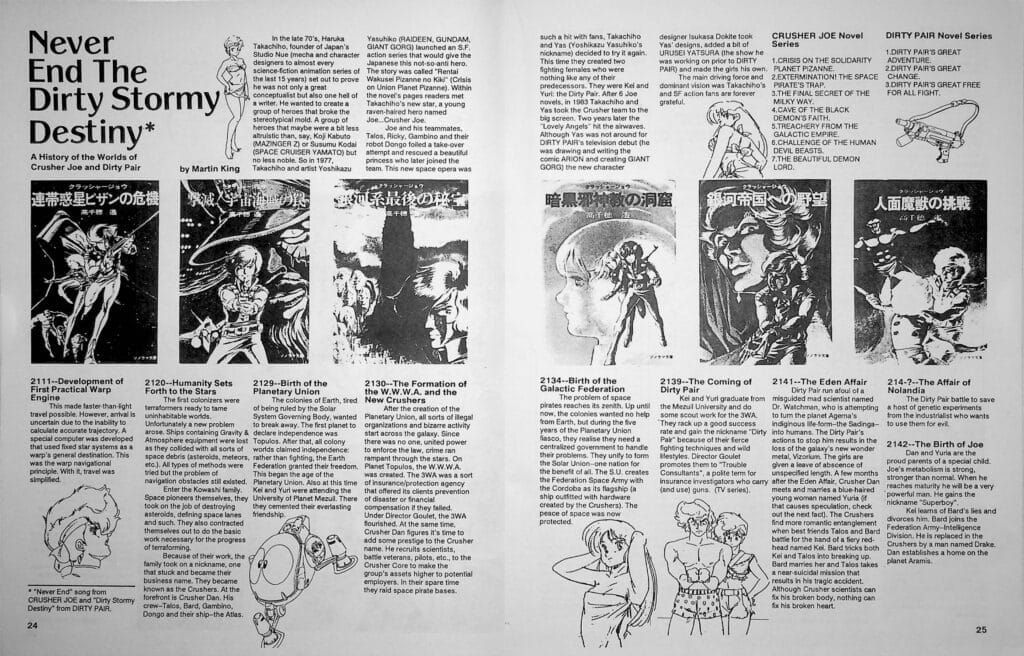

Lynn Morton and Martin King did some translations of scattered little articles here and there over years worth of various different anime magazines from Japan and came up with the plot line of what the 52 episodes would be—a synopsis. Years later, in 1993, I met Yoshinobu Nishizaki personally. And I’ll tell you about that later. But long story short, he was amazed that anyone in America knew that there was going to be more episodes and what the plot line was. I was very happy with that. When we were doing Dirty Pair as our cover issue number 3, Martin King, again, did an article on the Crusher Joe series of novels and the relationship between Crusher Joe and Dirty Pair—same science fiction author. But the fact that *Kei from Dirty Pair was Crusher Joe’s mother was a big reveal to me when I first read his article. And it was kind of a scoop.

(Interviewer’s Note: It was Yuri)

Kennedy (Red Bard): Do you have any other favorite articles or favorite content from Anime-Zine you’d also like to mention?

Robert Fenelon: Well, we talked about Saint Seiya, which had still been in its first series when we published. And all of the stills from the Saint Seiya article were from my personal cel collection. Because Bev, Mary, and I had gone to Tokyo on business, and on… It wasn’t New Year’s day because we were at Asakusa Temple. The day after New Year’s Day, I can’t remember what the Japanese call that—I think it’s a holiday—we went to Toei Animation out in Shakujimachikoen, I think is where their big office was on the Red Line, the Odakyu line. And on the forlorn hope that someone might be there, and maybe we could buy some posters or something, and knocked on the door, was met by this gentleman who looked exactly like a British college professor, right down to the sweater with the leather elbow things. And we asked him if we could buy anything, and he was surprised and brought us in. It turned out that that day every year they sell animation cels wholesale to wholesalers. And I could not convince this guy that we did not come halfway around the world just for his sale. So he let us in early, he let us look throughout the various tables. They had tables the size of pool tables with three-foot-high wooden borders around them that were piled in cels. And the center of the pile would be about five feet tall. Each table had its own series, which were different cels. When I found the table with Hokuto no Ken, and I mentioned it, Mary and Beth basically ran over, shoved me aside, and started pulling up cels from Fist of the North Star. So I wandered around and I saw another table that had really cool armor designs, reminded me of Jack Kirby’s Thor comics from the 1970s—y’know, helmets with big spiky things on them—and a lot of really weird choices for their color balance. I know some colorists in the comic book industry, and none of them would ever put magenta and aquamarine together in the same costume. But that turned out to be Andromeda Saint Shun. Pardon me, Dragon Saint Shiryu. And I was looking through the cels and I said, “Hey, Mary, there’s this cel over here with a guy with long black hair.” At which point, the feeding frenzy encompassed that table and I was shoved away.

But that show ended up being Saint Seiya, which we didn’t know because we’d seen the Saint Seiya manga in… Shonen Jump? Well, whoever was publishing it. And Masami Kurumada’s style is extremely heavy black magic markers, even more so than Doug Wildey’s in America who did Jonny Quest. And the character designs in the comic did not look anything like the cels from the animation. So we bought a bunch of the cels just for, y’know, “Well, this looks cool.” Not that we’re intending to sell them when we come back to America. And there was this pretty little girl in pink armor with long green hair, and I got all the cels of her.

And when we came back to America, the people who drove us from the airport to where the Moriarties were, we got there. John Carr—who’s a big-name fan from New York City—discovered the Japanese animation grocery stores and video rental stores that catered to the Japanese expatriate community. He was always renting tapes of Japanese television for us to see, had brought over tapes of Saint Seiya. And watching it for a little bit, it’s like, “Oh, my God. This is that Kurumada manga.” And the character design cleanup was beautiful. Shingo Araki, I think, made them look more like Rose of Versailles characters than Kurumada characters. Then Mary Kennard found out that the pretty little girl in pink armor was actually the bishonen of the show, and her favorite character. And she wanted a trade. I said, “Well, you know that Sayla Mass cel you have from Gundam that you never wanted to trade?” That’s how I got my Sayla Mass cel.

But yeah, Saint Seiya was a hoot. And all the cels in all the images in issue 2 on the Saint Seiya article were from my personal cel collection. And the cel of the dragon effect out of water chomping down on the black dragon doppelganger guy—I really wished I could have done that in color, and I kept pissing and moaning about it to bed that I really wish we could have done that in color. And she ran the numbers and said, “Okay, we’re going to have color pages next issue.” So the origin of our color pages in the fourth issue that never happened was me pissing and moaning about the Saint Seiya cel that was in black and white. That’s a pretty good memory of Anime-Zine. You asked about letters to the editor?

Kennedy (Red Bard): Yeah, just how many you received, if you remember. I thought that might help quantify maybe how many people were reading.

Robert Fenelon: There were very few letters to the editor that I chose not to publish. Almost all of them got published. And in each issue, there were two letters to the editor that I had ghostwritten because I wanted to use it as a question-and-answer session on some topic that we didn’t have the room to give it its own article in. It would be a brief bit of information. So if you count up the letters to the editor in all three issues, minus out six of them, that’s about how many letters to the editor we got that were grammatically capable of being reproduced.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Okay. Now, you touched on this earlier, but I was hoping you would expand on this: What caused the sudden end of Anime-Zine?

Robert Fenelon: The fact that there was nobody minding the store; the company had fixed monthly expenses, the company had some debt to service—not much—and the fact that no one was doing anything. No one was selling any merchandise, no one was publishing the magazine, no one was selling the magazine. We had no revenue coming in. We had expenses and we had obligations. We had subscribers who spent $10 and wanted to get some more issues. And fortunately, because of Ianus Publications—and especially the cordial relationship with Claude Pelletier and Laurent whose last name eludes me right now—we were able to satisfy those outstanding with Protoculture Addicts. But we had too many months of no work going in because Mary had already left the company and gone to Japan, and Bev was in the hospital with a stroke, and I was flat on my back in the most amazing pain I’d ever had in my life. And none of us were in any shape to do a lick of work and that killed the company. We managed to pay off all its debts and then got the IRS to shut it down.

Kennedy (Red Bard): And when was this—when the IRS shut it down?

Robert Fenelon: Probably ’86 or ’87. It was actually a joint stock corporation. It wasn’t a sole proprietorship. It wasn’t a bunch of fans putting it together. It was not an S corporation. It was an actual, real joint stock corporation. The shareholders—well, me and Bev and Mary were shareholders—there were a bunch of other shareholders. We couldn’t make them whole, but we could get them pennies on the dollar. And nobody’s been complaining to me since. But we were able to pay down the debts and get rid of the company. And I really wish we could have done it. I really wish we could have done it, but I cannot describe how crippled I was.

It was at least a half a decade before I recovered enough to drive a car again. I didn’t sue the guy who hit me. And a couple of months later, he killed his entire family and himself in a drunk driving accident. I was stopped at a red light and he slammed into me. I had a giant station wagon from the ’70s, and he pushed me five car lengths ahead and up a hill onto someone’s front lawn. And a cop came along literally instantly afterward, pointed to the—well, not instantly, because the guy got out of his car. He hadn’t been wearing a seat belt, so he was bleeding out of his eyes and his nose and his ears. And he said, “I’m okay, I’m a doctor!” And he staggered down the street. And someone who’s got obvious injuries, I’m not going to try to physically restrain them. He wouldn’t listen to me. He left. Cop came over, said, “Is that your car?” I said, “No, officers, that’s mine.” He said, “Uh, where’s the guy from the other car?” I said, “Follow that blood trail.” He’d been a drunk driver on multiple occasions—and I suspect he was driving with a suspended license—but he fled the scene. Turns out he was a county freeholder in Essex County, New Jersey—and a doctor! Someone like that has no excuse for driving drunk. And I was very bitter for a very long time. I have no tolerance for people who drive when they’re impaired for obvious reasons.

But yeah, I had to drop out of college—I was an undergrad at the time. I lost my job and my parents threw me out of the house and the Moriarties took me in and they paid for my medical bills. I went to a bunch of orthopedic surgeons who always gave me the same song and dance: “Oh, we need to tighten up that tendon and we can’t because there’s too much chance of paralysis or death, so we wouldn’t do the surgery. Here’s some drugs for painkillers.” Every. Damn. One of those orthopedic surgeons gave me prescriptions for addictive drugs. “So use it for two weeks and then renew it.” It’s like, “No! The literature that accompanied this one—I bought it—said that you can’t use this for more than two weeks. And after the third orthopedic surgeon I went to, they said, “I can’t help.”

Oh! Another thing they always said is, “Don’t go to chiropractors. They’re evil.” So after the third person told me, “I can’t help you. I want to push some drugs on you. Don’t go to chiropractors.” I went to chiropractors. And I went through five of them. The first one was just a pain guy. He wouldn’t do anything about what the problem was, he’d just treat your pain. The second one was a kook—a new-age guy, “Ooh, mystic forces flowing through your spine!” I fired him on the spot. The third one was good. He was a friend of my parents, but he was too far away, and getting a ride there and back would undo a lot of the good that his adjustment would do. When you’re in a car, you’re getting something called micro shocks, and that upsets the muscles that are supposed to be holding the bones in place. I eventually found a chiropractor in my town who’s fantastic and did a lot of good for me. Now I see the chiropractor a few times a year. Three out of four chiropractors I went to were useless. One was good, but too far away, and one is great, and I’m still using them.

It was a year, by the way—I didn’t mention this—it was a year between my car accident and when the pain started. Like an idiot, I said, “Well, I’m okay. Because I had two tons of Detroit steel wrapped around me when the guy hit me. I had a crease in my rear right corner panel. His engine was in his passenger seat.” If he had a passenger, they’d have been dead. So I was really smug that I wasn’t hurt. So when the cop said, “Go get an X-ray.” I didn’t. My atlas vertebrae has cracks in it, and the tendon on the right side of my neck that holds the atlas and the shoulder—ties all that stuff together—was overstretched and too weak. And for a year, I was walking around with a broken neck. The muscles and tendon that are supposed to hold it in place, were not. When I finally went to an orthopedic surgeon and they X-rayed me, they told me how outstandingly lucky I was. If I did a bad trip or a bad fall, or someone slapped me on the back between the shoulder blades, it might have severed my spine and killed me.

I was walking around for a year with that and never knew it. And then what happened was—yeah, it sucks to have a broken neck. At least it didn’t kill me. I always had my seat belt with a shoulder strap on, and I had my headrest up, and that saved my life. But two of the bones in my spine, one of them was out of alignment and was leaning over and pressing on a nerve. And that was causing immense—way worse than I broke my leg skiing, way worse than the surgeries I’d been through, way worse than I’d crushed one toe under a boulder.

It was indescribable pain, and it would not stop. And it visibly aged me a lot in a very short period of time. But eventually, I have recovered enough. I mean, I’ll never be able to go skiing or ride a horse again. I’ll never be able to go mountain climbing again. And these are things I used to do in my spare time—I stopped skiing, by the way, when I got into science fiction fandom. I did a relative cost analysis of how much it would cost me to buy new ski equipment and how much it would cost me to go to twenty conventions in one year, and the conventions were cheaper. So I stopped skiing. That was years before. And y’know, that was just buying new boots and new skis because I was about at the end of the lifespan of my old equipment. And then at the time, a lift ticket for the chair lifts to take it to the top of the mountain was $70. And that was 1981, and I’ve never skied since. But if I wanted to ski, I couldn’t.

I can’t water ski anymore. I can swim fine—water is great—but water skiing would be too great a risk. I can’t ride a horse anymore, which really, really sucks. My mentor, Colleen Winter, is one of the people who started me out on all this. I had taken a horseback riding course at my college, which I suckered my parents into paying for because they met each other during the Great Depression at a country club—they met riding horses. So that was one class that I managed to get them to pay for for a change. And I learned a little over the course of the first seven or eight weeks. Then I went down to visit Colleen one weekend, and she had a horse stabled nearby. And in that afternoon, she taught me more than the instructors at the horse riding class ever did. And when she designed my Desslok costume, it was designed to be working clothes.

I actually rode on a horse wearing the costume. Without the cape—you don’t want anything bumping into the horse’s butt when you’re riding. But I was at a convention in California where there was a guy who was doing the cosplay of Gato from Gundam Stardust Memories. And he dropped the microphone halfway through his routine and then just projected his voice to the audience and didn’t pick it up. Later on, there was a group skit on and I asked him, “Why didn’t you pick up the microphone?” He said, “Oh, if I bend over, this thing will fall off.” It’s like, “That’s terrible. Your costume should be able to take some wear and tear.” Mine was designed like any regular clothing would be designed.

I was cosplay judging. I used to judge cosplay. When I stopped actually participating in cosplays, I ended up judging for a bunch of years. And there was this one guy, came on with a Mobile Suit Gundam costume largely made out of styrofoam, that was something like ten feet tall. There was something like, a foot of styrofoam under his foot to the floor. And you got a five-minute limit in a cosplay, and there’s a ramp leading up instead of steps. This guy got halfway up the ramp and his costume fell apart on him.

Then there was one convention where the judges, we were leaving—the cosplay was over—we were leaving and saw this guy who was wearing an Evangelion costume of the purple Eva that Shinji drives. And he had the Spear of Longinus with him. And it was made out of wrought iron, and we asked to see it, and it was one piece of wrought iron that had been split at the top into the fork, and the whole thing was curved, and the guy had forged it himself. Our craftsmanship judge was practically in tears. She said, “If you had come up on stage, you’d have won!” The guy was thin as a rail, so he could actually pull off an Evangelion design. He was skinnier than most humans. And he had hair down to his waist. From the back, he looked almost like a Saint Seiya character with his helmet off.

I was lucky when I was a judge. There was always someone in the judging panel who played video games, which I don’t. So anytime there was a cosplay based on video games, well, my weakness as a judge was not revealed. I was always pushing to give more prizes because I wanted to encourage more and more people to do cosplay. I thought four prizes was stupid, so I was always pushing for judge’s prize awards, judge’s choice awards, and things like that. There was one cosplay where they had a bunch of people come up doing the Darkstalkers Vampire Savior video game thing, and unfortunately, it took more than five minutes, so they’re disqualified. But there’s a character in that OVA series—and I presume in the video game as well—there’s this little girl who’s walking around scowling all the time. The only noise she makes during the series is, “Hmph!” It’s the last episode when they get her to open up. And this little girl came up when everyone else was done, moved the microphone down so she could reach it, went “Hmph!” and walked off the stage.

My judge’s choice award was the best use of Mushin in a cosplay. And one of the cosplay judges was this young Japanese woman who was a manga artist named Ippongi Bang. And I had to explain to her and her staffers the Zen Buddhist concept of Mushin because they’d never heard of it, which was kinda goofy. There was an AnimeNEXT convention in Secaucus, New Jersey, right across the river from the Meadowlands. And we were having a discussion with the Japanese guests about environmentalism and pollution. And Brian Price was mentioning to them about how Miyazaki had based Nausicaä and the toxic jungle on mercury poisoning in Minamata Bay in Japan. And in the Minamata Bay thing, there was a whole bunch of mercury poured in and it killed the Bay—like there was nothing alive, not even algae. And then years later, life started coming back to the Bay and they did some research. Some form of algae or other really tiny thing had been growing little colonies around each droplet of mercury and creating a cyst around it and falling to the bottom of the ocean. And this is a process known as chelation in either chemistry or oceanographics, I don’t remember. They were chelating the mercury out of the poison bay. It got to the point where you can fish there now. And how Miyazaki based the toxic jungle on that where it was basically taking the poisons out of the land and processing them and making the land livable again. And we were explaining this to the Japanese guests, and I said, “Yes, and it’s already started.” They said, “What?” And I said, “There’s a place on earth that is so polluted with heavy metals that if you take the plants out of it and plant them in normal soil and normal water, they will die. They require the pollution to live.” And they said, “Where is this?” Channeling Peter Cushing, I ran over and tore the drapes away from the window and said, “There, the Meadowlands! That is fukai—that is the toxic jungle!” It was a wonderful moment of performance.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Circling back to Anime-Zine, after you had recovered, did you ever consider reviving Anime-Zine?

Robert Fenelon: No. It was too painful. It was too many bad memories. It was the biggest failure of my life. I was not interested. Now, one of the great tragedies of Anime-Zine is we were biting off more than we could chew. We managed to keep it going, and only the fact that we were selling more issues than the previous issue was keeping the thing profitable. If we ever ended up at a point where our sales started going flat, I don’t know what would’ve happened.

But it started smaller than it became, and we were thinking smaller than we ended up being. But one of my great regrets is I never listened to Bev. She said, “Look, write your own articles yourself. You know more about this stuff than most people. Write your own articles.” But I had this weird journalistic integrity—misapprehension that since I was the editor and co-publisher, it would be wrong to showcase my own work in my own publication. That’s a decision I regret because there were issues that were delayed waiting on articles that other people were writing. Except for that third issue—when we’re talking about the fourth, we never committed to what we were coming out with in the next issue. So no one would know if there was a last minute substitution. Keeping on a tighter schedule would have made it a more profitable magazine.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Now, just a moment ago, you referred to it as your “greatest failure.” Are you referring to Anime-Zine?

Robert Fenelon: Anime-Zine and Minstrel Press is because, well, okay, failed promise. There was a lot of promise there that we never achieved. It was going to be better than it was, and it died. And part of that is my fault. I was sitting there at the red light and I looked up in my rearview mirror, I saw the guy coming and didn’t think anything of it, and I looked up and saw him closer, and I pulled my foot off the brake to put it on the gas, and he hit me. And the fact that my brake was off—disengaged—I didn’t even reach the gas pedal before he hit me, he was going so fast. The fact that my brake pedal was disengaged probably saved my life because a lot of the kinetic energy was used to push my car forward rather than going into the car and myself. But if the first time I saw the idiot coming and realized he was coming right towards me instead of going to the left of me—or the right of me, I should say—if I pulled my foot off the brake earlier and stepped on the pedal earlier, things would’ve been different.

I consider it a failure that Anime-Zine died so early. It’s a big regret in my life. It’s a huge regret in my life. I’m happy that it happened. In my life, I’ve known a lot of artists and authors, and they leave their work behind. And even after they passed away, people are still enjoying their work. It’s something permanent, whereas the work in my life as a historian is extremely minor. But Anime-Zine is something I created that’s out there that… Well, the fact that you’re buying used issues on eBay proves that people are still seeing it. That’s something I’ve created that will be a legacy, and that’s great! I love that! I just wish that we hadn’t gotten that triple whammy at pretty much the same time.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Were there any leftover issues of Anime-Zine at the time that hadn’t shipped out? What happened to those if so?

Robert Fenelon: Oh, no. Issue 3 had been shipped.

Kennedy (Red Bard): No—did you have any extra boxes of issue 3 that had not yet been shipped is what I mean—or 2 or 1? Basically, were there any extras at the time?

Robert Fenelon: There were extras. I’ve got at least a dozen left. But at the time, I held back one or two boxes. That’s 200 or 400 copies, or 150 or 300 copies. However many fit in a box back then. But those, yeah, they stayed behind. And I was able to show people those and give them—I’ll send you a copy of number 3 to complete your collection!

Kennedy (Red Bard): Thank you! I appreciate that a lot! That is honestly so cool.

Robert Fenelon: Well, I must admit that I have a weak spot in my heart for anyone who’s researching history and sharing it with the public. I’m very positively inclined towards you, so I’m happy to do it.

Kennedy (Red Bard): That’s very kind of you to say. Thank you!! So, what do you think made Anime-Zine so special?

Robert Fenelon: One of the reviews at the time—which still exists and I saw recently—said that unlike the other anime magazines, it was oriented towards the fans instead of towards the companies. A lot of the other professional animation magazines that got nationwide distribution that came after me had a lot of press releases and a lot of information they got directly from companies, studios, distributors, whatever. If you know where to look, you can see the corporate spin. Whereas with Anime-Zine, it was just people writing about these shows and saying, “This is cool, check it out.” We were always trying to find a little trivia to add in there. Like I said, with the letters to the editor column, I would sneak in little conversations of questions and answers—2 per issue—with topics that we didn’t have space to do in the rest of the issue.

And the sidebar that we did with Pat Malone, where she was talking about Miyazaki basing the costuming of the Valley of the Wind people in Nausicaä on Polish costuming from late Middle Ages, that we wanted to continue—we went to a Philly C/FO meeting and we were selling copies. We’d basically given a bunch of copies to some dealer and he was selling them. And Bev and I were in another room—not watching the TV, but talking with people—and somebody came in and started spouting off information about Nausicaä‘s costuming. It’s like, “Okay, this guy had read the book and read the magazine, and he was immediately going around sharing the knowledge of this little trivia thing we stuck in there. So future issues, we’re going to have a lot of little sidebars and boxes that’d be like a quarter of a page, or a half page, of just some obscure little trivia about some anime that had nothing to do with the rest of the magazine.” Because we thought that would become a real selling point, is the little trivia things that people would share among themselves.

This was before the Internet, of course. *1986, I think, was the last year we were publishing Anime-Zine. World Wide Web was created in 1991 by a couple of French doctors at a conference in Europe. They wanted to send a paper through the phone lines to an American colleague of theirs—that was the beginning of the Internet.

(Interviewer’s note: *1987 or 88.)

ARPANET existed, of course. ARPANET was connected to colleges. So if you had a college that was a research college and you could bluff your way into their computer lab, you could talk to other people on ARPANET, like bulletin boards and conversation things. There was one on Yamato that had a hell of a lot of people. I think 1983 was the first time Walter Amos got me on that. He’s a rocket scientist, used to work for NASA in Texas. And now he’s writing GPS code for the next generation of GPS. And he’s back in Philly. And he ran a Star Blazers discussion group back in the early 1980s that tied together all the big names in Star Blazers fandom and people were sharing information and talking and it was really cool. But that was about it for the Internet. No pictures, no videos, just people typing words. And it was like a big mailing list more than anything we see on the Internet today. There wasn’t the easy access to trivial information that we have now. So putting that little trivia information in the animation would give people a lot of what you can now get by just searching on the Internet. And that was cool. We were looking forward to that having a good effect on our sales. And I’ve gone completely astray. What was your question again?

Kennedy (Red Bard): I was asking, what do you think made Anime-Zine so special?

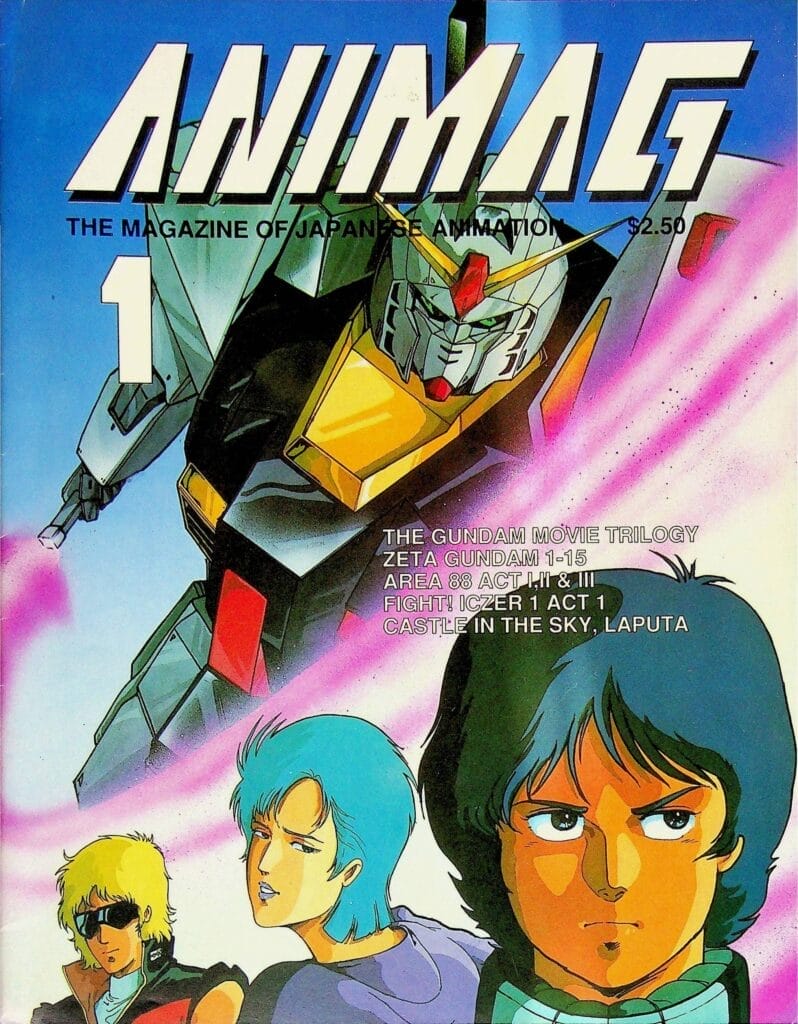

Robert Fenelon: A lot of content, a lot of dense content. And we weren’t always talking about the latest, greatest thing. We had articles on older animations, and I think that helped a lot. Animag was the next professional publication to come out and be distributed nationally. And I got a phone call from Matthew Anacleto, who was their editor or publisher at the time. They printed out their first issue and they had some problems, and he somehow found my phone number and was asking me for advice. And he was having a problem where Nippon Sunrise was coming down on him like the wrath of God, because his entire first issue were all Sunrise copyrights.

Now I had—in preparation for when Bev and I were putting together Minstrel Press—I took a course of independent study in my college in the law department on the copyright law. So I read Title 17 backwards and forwards and had some pretty, pretty awesome experts at the college that I could go questions and answers with about how copyright law works. So I knew a lot about the copyright law as it was written back then. And I advised them, “Look at Starlog or Anime-Zine. No more than 33% of our content is on any one copyright holder’s various properties. That’s because the copyright law says you have to have a substantive proportion of your publication be one copyright holder to be actionable for a lawsuit.” Starlog decided that it wasn’t like 49%, it was 33%, and I decided that they’ve been publishing longer, they know what they’re doing, I’ll do what they do.

The substantive proportion is largely up to whatever the judge thinks. Copyright law is—even back then—was a shuffling monster of the law. And it’s only gotten worse. But I explained to him this, and I explained to him, “Look, you’re in trouble because you’re completely actionable. Your entire book was their publication, and you’re making money off of it. So you will lose a lawsuit. So don’t let the lawsuit happen. Go on the offensive, attack them.” And I told him, “Here’s what you do: Contact Sunrise, and you don’t say, ‘Oh, I’m sorry I stepped on your toes.’ You say, ‘Oh, but I want to be your publicity organ in America. Give me information, give me cells, give me stills to use, give me articles on your stuff, and I will be your publicist, and I will publish your stuff in America.’” I said, “Because you’ll lose a lawsuit. Don’t play defense. Go on the offensive.”

And they gave him not only that, they gave him a huge chunk of money. And the second issue of Animag was absolutely beautiful; double gatefold covers—both the front cover and the back cover—folded out to 2-page posters. They’re on *Aura Battler Dunbine, which was a property that Sunrise was trying to sell at the time in America. And it was gorgeous. Animag got a lot of—I don’t know how much money, but I would say, sheetloads and sheetloads of money. And they produced a really beautiful publication. They had a lot more color pages than I even imagined we’d have in issue 4 of Anime-Zine.

(Editor’s note: Dunbine is on the cover, but it’s not the subject matter for the posters: per a scan of the magazine on Archive.org, the posters appear to be for Arion and Iczer.)

It could be because Anime-Zine was there first. It could be that Anime-Zine was all over the country. It could be that Anime-Zine was less an organ for publicity for studios and more people writing about what they loved. It could be that we had a lot of dense information in there. We didn’t have any fluff in there. We didn’t have any space filler. The articles are fairly densely written and communicating a lot of information. And we tried getting information that no one knew. Martin King and Lynn Morton did the translations for the, “Here’s the original 52-episode version of Yamato 3 we never saw because it ended up only being 26 episodes because it, too, was canceled just like Yamato 1.”

And when I met Mr. Nishizaki in 1993, there was—the copyrights for Star Blazers had been up for grabs. And the copyright that Westchester films had—that’s Claude Hill, the guy who brought it over to America and hired Kit Carter to cast it and direct it and dub it—he had lost the copyright and Nishizaki was renewing it for six months at a time, but asking for more money each time. And Nishizaki eventually decided to go sell it elsewhere in America. And Floyd Hill had all the derivative copyright. He had titles of the derivative copyrights. He had titles to every English language name. He had titles to the word “Star Blazers” itself—those are all derivative copyrights, not actual Yamato copyrights.

And he was going to start a comic book company. He’s a man who tried to buy Marvel comics once and almost got it in a sealed auction bid, but Revlon outbid him. And Revlon—the shampoo company—ended up owning Marvel comics for a few years after that. But he wanted to start a comic book company. And we had a bunch of people from DC and Marvel like Dave Cooper and Martin King, and… I can’t remember his name, he lives like four blocks away from me, this is so sad. But we were going to do a Star Blazers comic book set fifteen years later. That way we could change everyone’s character design and update the ship so that we change its design. So it wasn’t actionable.

Brian T. Price: Was this Matt Lunsford?

Robert Fenelon: Thank you! Matt Lunsford was one of the artists from Marvel Comics. The guy who created the Inhumanoids from that cartoon? He was a Marvel comic artist.

Brian T. Price: I don’t know if Lunsford had anything to do with Inhumanoids, but I know he wrote it.

Robert Fenelon: No, you’re right. It was an older, fatter guy who created Inhumaoids. But Lunsford was one of the people we were talking about. And Claude Hill had the rights to Marine Boy—or he secured the rights to Marine Boy because for a while, no one knew who had the rights because the last rights holder in America was Seven Arts. They stopped being a television company and started producing office equipment and burned all their old records. So they didn’t know who had it after them, and it took a long time for Claude Hill to get the rights to that. But there was a title called Rocket Robin Hood, which is a science fiction. There is this silly history thing called Max, the 2000-Year-Old Mouse, and we’re going to update it as Max 2000, give him a time-traveling watch, make him half Doctor Who. And the character designer for that comic, Keisha Wilkerson, gave him Kimba the White Lion’s forelock.

So we had these titles, and I went with Martin King to talk to Yoshinobu Nishizaki to see if we could secure the rights to do a comic book, as in we could use the Japanese names and stuff. And I was the last interview he had that day. He had a hotel room and he had Chikako Lorenzetti—who was an extremely accomplished translator and lawyer—was accompanying him. He’d had half-hour meetings with all these people who were trying to buy Star Blazers. And then Martin and I came in as the last interview of the afternoon. And we started talking and I said, “Well, first of all, before we start, I just want to tell you what an honor it is to meet the man who was Dr. Tezuka’s agent.” At which point, Nishizaki’s two subordinate executives whipped their heads around and said, “You?!” They didn’t know he was Tezuka’s agent back in the day—that’s how Nishizaki got his start in the animation industry.

Then I referred to Triton of the Sea—an anime series he produced way back when—and we started talking. And when Martin showed him the article about the 52-episode version, it stopped being a negotiation to buy a license, and became Nishizaki, me, and Martin as three geeky fanboys all talking to each other about this show that they loved. I had six hours with them that afternoon. The only reason it was cut short was Chikako showed up and said, “Our opera tickets, we have to go now!” Because Nishizaki is a big fan of opera—was a big fan of opera. I think the first tragedy of his life was that months before the live-action Yamato movie came out and the world would’ve beaten the path to his door—he would have been happy giving interviews to everybody—he got drunk and fell off his yacht and died, drowned in the ocean. That really sucks. If he’d only stayed alive a couple of months later, he would’ve had a really high point in his life.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Circling back to Anime-Zine, do you still get asked about it a lot?

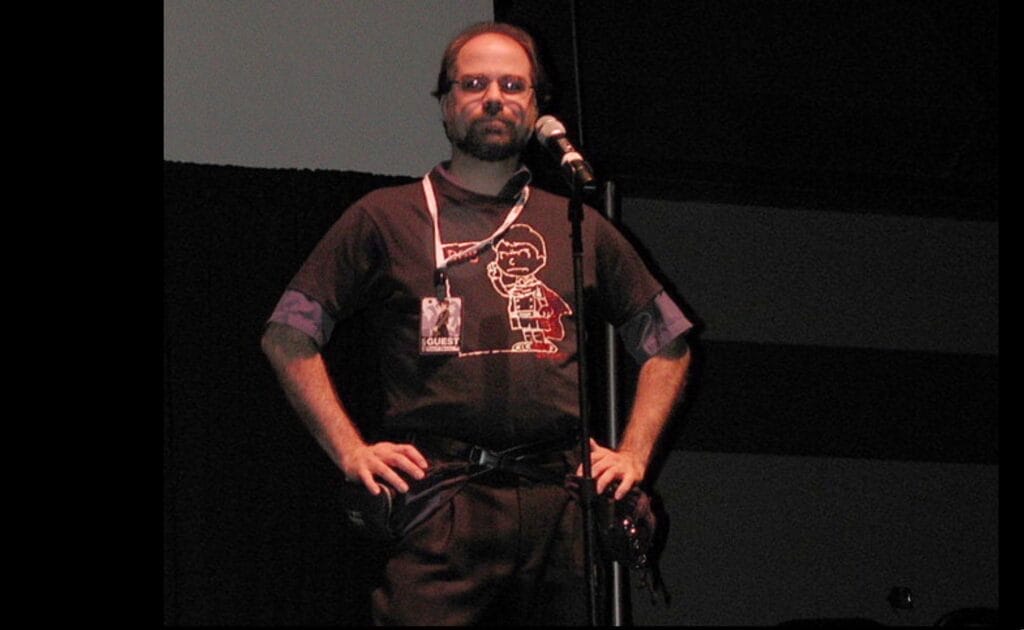

Robert Fenelon: Yeah. Yeah, people mention it. One of the panels that Brian Price and I do at anime conventions is we talk about old-time fandom—what it was like back in the before time. Brian made up a panel called Anime Older Than VHS. Y’know, anime at the very beginning of the start of it.

Brian T. Price: Geezer panels have a long history! There was a geezer panel at the Otakon that I got stranded at in ’97. It’s just a matter of coming up with different names for it—it’s better than just calling it “The Geezer Panel.”

Robert Fenelon: They’re always popular at conventions. And we did a geezer panel—the Older than VHS—at Zenkaikon in Pennsylvania a few months back. And if you go to Zenkaikon’s website, I think there was a camera in the room, they may have recorded the whole thing. And you can watch it, and you’ll see that Anime-Zine does come up. And there’s a bunch of other stories we told them about what it was like in the before time. And it was a really good panel because I got off the stage and was walking in the audience, talking with them, which is always a good sign.

Brian T. Price: Well, when we started breaking out pictures, like some of the pictures that you posted earlier—

Robert Fenelon: Oh, right! From the stage where we were sitting behind the microphones, we couldn’t see the screen.

Brian T. Price: Yeah, it was directly adjacent to us, so we would’ve had to have been leaning over the table just to see. So we’re just like, “You know what? It’s a small enough room, we know how to project our voices.” So we just went out amongst the front of the crowd and just started pointing.

Robert Fenelon: Yeah. Saying, “This person is that, this person is that.”

Kennedy (Red Bard): After Anime-Zine, did you ever get involved in any other anime magazines or anime-related writing?

Robert Fenelon: Yes. I was an early, unpaid consultant for Animag. Like I said, he called me for advice and I gave him advice, which he took and profited thereby, which I feel a little proud about.

Brian T. Price: Trish and Toshi?

Robert Fenelon: No, before—it was Matt Anacleto and when Sunrise was going to sue them because their first issue of Animag was all Sunrise properties. I think they had half a page that wasn’t a Sunrise property.

Brian T. Price: Animag was my first ever anime-related magazine.

Robert Fenelon: Animag was slicker and glossier than Anime-Zine. Animag is slicker and glossier than Anime-Zine would have evolved if we kept going. I would have opted for—when we could afford it—a perfect binding, square binding, which would make it easier for libraries to buy it. One thing I used to do to make money—cause like I said, I was unemployable after I broke my neck and this being before the Internet, it all had to be done by fax and phone. And I had some clients in Japan, so I got some very bad habits of staying up way too late in the night and early in the morning. But… Where the hell am I? What was I talking about?

Brian T. Price: Animag, or other other publications you’ve worked on.

Kennedy (Red Bard): Yea. Any others you’ve worked on, be it magazines or whatever else.

Robert Fenelon: Well, okay, let’s chalk it up to the senior moment. I don’t remember where I was going to go with that. But I wrote for several Antarctic Press Publications. I’ve known Ben Dunn and Douglas Dlin forever. They’re the guys down in Texas who are pretty much the brain and the backbone of Antarctic Press. Yeah, I met Ben Dunn, I think, in 1981 or ‘82 when he just started publishing Ninja High School. And I remember telling him, “I love those first three issues. It reminded me of Prefectural Earth Defense Force.” And he’s like, “Finally!” Everyone had been telling him it reminded them of Urusei Yatsura—Those Obnoxious Aliens. But he’d been basing it largely on Kenritsu Chikyuu Boueigun, Prefectural Earth Defense Force—which is the absolute funniest fiction I’ve seen in my entire life. I can’t recommend it to your readers highly enough.

But Antarctic Press, I wrote a couple of articles for on Star Blazers, probably on early anime history, I don’t know what else on. They had a publication called Mangazine that talked about manga and some anime. I think I might have done a history of early animation fandom for them. God, I wish my memory was better. I don’t think I wrote for anyone else who was professionally publishing animation magazines.

Ardith Carlton—my ex-girlfriend—she did some really good articles in Comics Buyer’s Guide on, one on Star Blazers and one on anime in general. And that helped create a lot of anime fandom—a lot of people read that and decided they wanted to go after anime. Lavishly illustrated from her cell collection. There was another publication I was involved in. I’d mentioned earlier that Frederick Kopetz in the Star Blazers Fan Club published the first APA that was based on anime—APA is Amateur Press Association. The first one was founded by Edgar Allen Poe.

What I would do for an APA is I would write up a couple of pages—some of my sections were 50 pages, some of my sections were less—about anime, about whatever I wanted to write about. I’d put in my own examples of my own artwork, stuff like that. And I usually had an article on some new animation that had just come out, and here’s what I can find out about it. This is way before you could look on the internet and look at Wikipedia and know stuff about it, because there was a huge timeline between when something was showing in Japan and when the videotape of it would make their way to America and make their way through fandom to my hands. So I would put up as much information as I could get as quickly as I can get and put it in this magazine. And I would do deeper dives into older stuff. One of my favorites was I did a fourteen-page introduction to Tezuka’s manga Vampire, which was about werewolves.

I remember there was a controversy in fandom where they’re saying, “Tezuka is stupid! He’s calling werewolves ‘Vampires.’” Well, here’s the thing: The Romanian word for blood-drinking ghosts is “vârcolac.” And the word for a skin-changer who puts on an animal skin and turns in the animal is “vampir.” Bram Stoker, when he brought the Romanian myth to England, decided he couldn’t call the vampire a warlock because everyone knows what a warlock is—he couldn’t have his blood-drinking ghost be called “vârcolac.” So he switched it and he said, “vampir”, rendered in English as “vampire,” whereas, in reality, “vampir” means werewolf, or someone who turns into an animal. And it was the first manga I ever bought.