Manga is one of the most exciting comic mediums to me. Thanks to its rubbery definition, the format lends itself well to stories that become love letters to the human condition and is able to explore the super-silly, the utterly serious, or even the horrors that lurk in between. As a teenager, I made far too many fond memories, just browsing the manga sections in Barnes & Noble and Borders.

In this day and age, though, when COVID has infected hundreds of millions of people and threatens to do so once again, I can’t, in good conscience, skim a volume of manga at my local bookstore. While I still purchase books for myself, and for care packages for others, I wouldn’t dream of potentially spreading the virus for such a selfish desire.

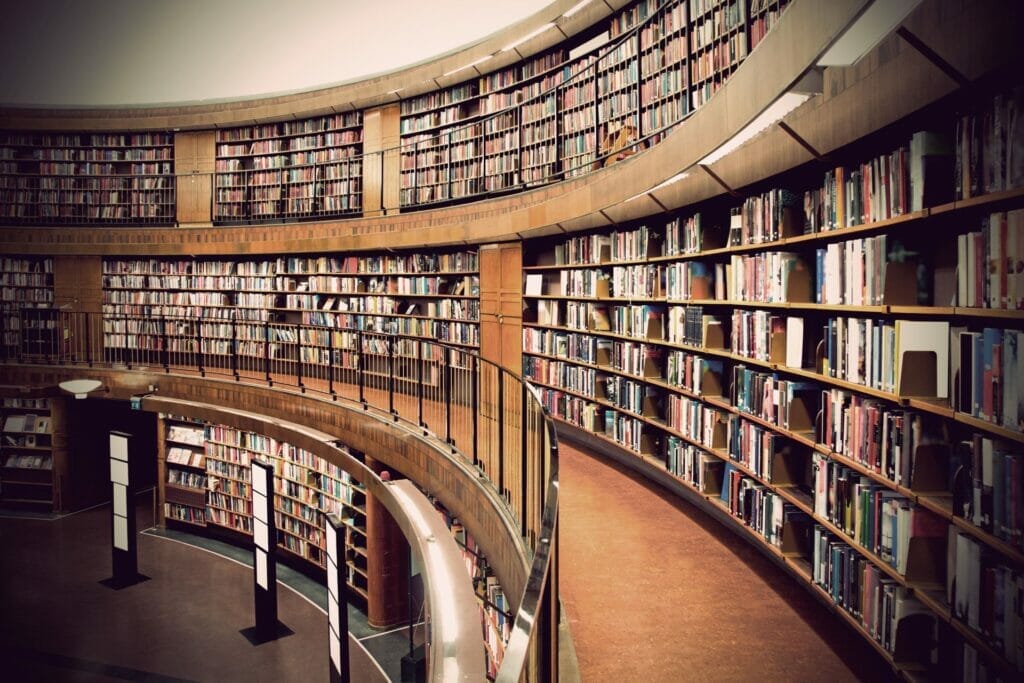

There is still one resource that is available to all, though: the public library. While every public library doesn’t maintain the same standards, and many are under attack in certain states, including my home state of Florida, there are ways that we can help hard-working librarians in these difficult times. What’s more, we help introduce more Westerners to good Japanese manga, and American comics that pay homage to their predecessors in the process.

Can Libraries Stock Every Manga Series?

In an ideal world, libraries would be able to stock every series, from the best known to the most obscure. In the real world, though, librarians can’t request to order every manga volume in existence. The sheer number of manga available in the West is far too great, for even the best-funded of facilities. That’s to say nothing of publishers like Oni Press, who also publish western manga-style works. “For me, it’s mostly keeping up with all of them,” San Francisco Public Library librarian Jaena says with a laugh. “I try to notice the circulation stats for specific titles, or I try to stay abreast of what popular animes are coming out.” They add that, “since most manga is paperback, maintaining the physical condition of these books remains pretty difficult […] Fortunately, SFPL has a healthy budget and we can typically reorder whatever we need. However, I think you’d be hard-pressed to find a branch with a complete collection of any one manga title.”

What factors may go into choosing a new series? Patron interest, for one, as well as ensuring that a healthy mix of genres is available for patrons.

“I am intentional about having something for everyone in the teen area, including romance, a slice of life, fantasy, action/adventure, LGBTQ, etc.,” librarian Thomas explains. “There is also the matter of gateways, so when a parent comes over with a curious child looking for something relatively tame, we don’t turn them away. Shojo and Shonen standards are the two big umbrellas for a lot of readers, who then branch out to ‘give me something like X,’ which then branches out to ‘give me something unlike X but still really good.’ The internet has empowered many readers into arriving at the library with a checklist of series to binge, and I am happy to oblige.”

Budget is another concern, as New York City school librarian Ashley details. “The first challenge at any time is that as a school library, I have a limited budget,” they explain, “The state only provides me with $6.25 per student each year, which isn’t even a book per student. So, I have to write a lot of grants in order to make ends meet. This year, I got incredibly lucky and was able to get a $200,000 grant. This brought in the second, current challenge: supply chain issues. Even when I have the money to purchase materials, I won’t necessarily get them because of issues with fulfillment related to the current supply chain. What often happens is that I’ll get random volumes. This means next year, a big part of my ordering will be dedicated to filling in gaps in series.”

No manga volume costs only six dollars; once upon a time, anthologies like Shojo Beat and Animerica Extra cost five bucks, but these magazines have long been defunct. If librarians have to do more work to reach the funding they need, that is a problem.

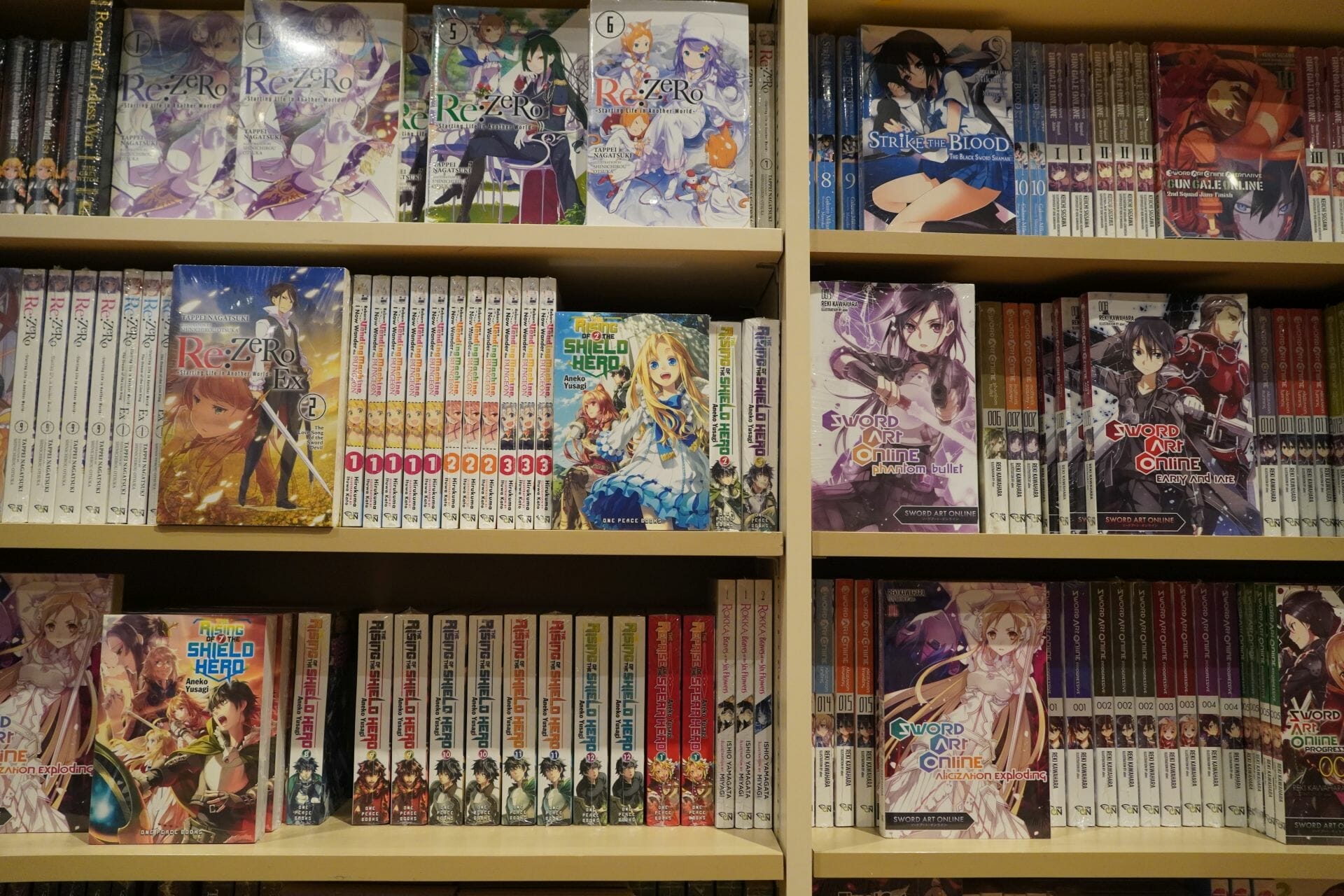

Long-Running Series

Many of the most popular manga series are long and ongoing, with a few extending to more than thirty volumes. One Piece is such an example, with more than one hundred books dedicated to the story of unlikely heroes becoming pirates in search of treasure, glory, and friendship. Relatable superhero story My Hero Academia is another, which clocks in at thirty-five books in the main series alone, to say nothing of its several spinoffs. Outside the Shonen battle genre that these series inhabit, readers can find numerous long-running magical girl stories, josei romances that seem to go on forever. How does one even begin to categorize the works of a prolific horror artist like Junji Ito, whose imagination never fails him when it comes to portraying the terrifying, or Yoshihiro Tatsumi, whose cinematic style defied and created conventions?

Shelf space is limited, and must eventually make way for other media. As a result, a library’s collection of long-running titles may remain incomplete. I speak from experience that it can be frustrating to scour the shelves for the sixth volume of a manga, only to discover that volume twenty is the sole installment available.

The librarians with whom I spoke mentioned that patron demand factors into their ordering decisions. “My process for most titles is that I buy a few volumes either because someone asked for them or because I thought they’d be well-received, and then if they get checked out I go to buy more,” Web and Systems librarian Rebecca explains. “I don’t want to buy twenty volumes of a series from the get-go that no one’s interested in, but if three volumes sit there, it’s not as big of a deal. We do have shelf space to consider.”

Budgets And Decision-making

Limited budgets often force libraries to make tough decisions regarding which books to carry, be they novels, comics, or manga. While patrons can donate books, there are usually rules and regulations in place to ensure that donations are not damaged, and do not add to excessive stock.

“But space is a big challenge for libraries, especially when it comes to One Piece in particular,” school librarian Ashley Hawkins explains. “Another challenge is that volumes will go out of print, and it can be hard to get a complete series. Shojo manga, in particular, will go permanently out of print very quickly, or will never be in print at all. This is actually where digital options such as Sora by Overdrive and Comics Plus by Library Pass can be a big help, but ultimately I’ve found that my students prefer having print manga.”

“The priority really goes to materials that support the college’s courses and curriculum so we’re not at the top of the list,” Web and Systems librarian Rebecca agrees. “Though, the fact that they get students into using the library and the fact that they’re way cheaper than the kinds of books we typically buy does help bump things up a bit. We’re also limited to what our book vendor has available; we can’t just go to Amazon or Barnes & Noble or some local shop and buy things, we have a contract with a vendor that we have to use for almost all of our purchases). Lastly, we have some limitations with cataloging-related things locally so I sometimes have to wait for there to be good-enough records to use to set them up for finding and circulating in our library system.”

I can attest that out-of-print works present a challenge, as someone who wished to read through Kiyoko Arai’s Beauty Pop, but could no longer find it in print, alas. Limitations caused by local catalogs can also present a problem, even if a reader is willing to wait for an interlibrary loan.

Current Manga Apps Lack Consistent Library Access

With the advent of ebooks, a number of apps have begun to work with both libraries and schools to provide access to more literature than ever. Libby and Overdrive are such examples, delivering audiobook or text loans to patrons that have a password. Librarians have split opinions on if the apps help the manga communities directly, though.

On the other hand, legal digital manga apps like Azuki and Shonen Jump both charge for monthly usage. Both offer the first chapter of a series for free and sometimes the latest three chapters depending on the title. Beyond that, though, Shonen Jump maintains a price tag of $1.99 per month, while Azuki carries a monthly $4.99 fee. Crunchyroll also includes access to a growing manga library for customers who maintain a regular subscription to their streaming services.

“I love Azuki, and Shonen Jump is an amazing deal, but neither one of them provides library access,” Ashley explains. “So they honestly do nothing to bring the manga to libraries currently. I pay for both for myself, and that helps me make collection development decisions, but that’s as far as it goes. I cannot share my accounts with students, as that would violate the terms and conditions. Honestly, library licensing is very messy and expensive, so I don’t see the current apps making that jump. Comics Plus is the closest to those apps, and then there are digital copies available through library applications such as Libby or Sora. Those copies are part of the library collection and are subject to holds, due dates, and so on.”

“They lower the barrier to entry, for sure,” Thomas disagrees. “I remember when the library had a print subscription to Shonen Jump and transitioned to digital. SJ was receptive to the idea of logging readers in on computers, but that method just wasn’t feasible when piracy sites already give away so much manga. At the same time, the price point on Shonen Jump’s price and library models encourage binge-reading a wide variety of series. Those readers step into the library knowing that much more about what they like, which helps the library decide what to order. During anime club meetings, teens bragging about how they tore through dozens of volumes of a giant series over a single week turns power reading into a social achievement. Apps that enable those teens and the quiet types are fantastic for growing loyal readers.”

Though they do carry their benefits, manga apps do raise the question of whether their availability cuts into the longer series’ demand from libraries. Rebecca explains, ” We actually don’t have any manga as ebooks in our library because the platforms we do carry have awful readers that are really designed for academic books. Instead, we refer people to the local public libraries. New York Public over the past two years has really expanded their ebook manga collection a lot and has the infrastructure for it, and all of our students can get cards for NYPL.”

Potential Solutions

In an ideal world, librarians would have the budget to order volumes of longer manga series. However, in many cases, local governments and nonprofits determine the budgets. Schools will determine their library funds allocation, with factors including if they are public or private. A budget change can determine if a librarian will need to choose between Perfect World or Food Wars.

How does one increase the budget for librarians? Fundraising is one option. Donations and sales from charity drives can help increase the amount of money that a librarian has to order a series. One can also buy these series and directly donate them to the library, ensuring that a high-quality version exists.

You can also get active within your community. Friends of the Library (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friends_of_Libraries) refer to a collection of groups that assist libraries with their funding, resources management, and community presence. Members can serve on library boards or as government advocates, to speak for various institutions. Getting involved can allow you to see how your local system works, and what your local librarians need to stock more manga.

Ultimately, much of the battle to bring more manga into libraries boils down to information. Many local libraries are run by local governments and nonprofits, while school library budgets are dictated by the schools themselves. For local libraries, it’s worth researching to see if they hold local meetings to discuss funding allocations, and if they keep time to hear citizen requests. These provide a powerful avenue for citizens to lend their support to librarians while letter-writing and phone call campaigns can allow organized groups of people to have their voices heard. For parents and students, school board meetings provide ample opportunity to advocate for librarians, while also offering a look behind the curtain, to see how decisions are made. Furthermore, these meetings are a good place to see if it’s possible to make donations that comply with school policy or to help the librarians that are applying for grants.

The best thing you can do, though, is to listen to librarians firsthand. They have seen the many potential opportunities to introduce an unknown manga artist to readers or to answer the question of “what happens next” when the latest volume ends on a cliffhanger.

“My advice to librarians just beginning the work of stocking manga is to start with the first few volumes of a series,” Ashley says. “See what the demand is, then make decisions about how you want to expand. Quite honestly, the most popular series doesn’t spend much time on the shelf. Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba is barely ever-present, and I haven’t put a volume of Tokyo Ghoul back on the shelf since September- they only ever make it to the return cart.”

While it often seems like a daunting task, we’re not powerless to help our local libraries thrive. Like the heroes and heroines that run through a great manga, if we rise to the occasion, even the impossible can be achieved.

Special Thanks To The Librarians Who Contributed Their Viewpoints:

Jaena: My name is Jaena Rae Cabrera. Pronounced “Jay-nuh.” I read a lot of fiction and it ranges from graphic novels to sci-fi to mysteries, etc. I actually started out as a journalist right out of college and worked for Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting as a web producer for nearly five years before attending library school and transitioning into librarianship.

I’ve been a librarian for the San Francisco Public Library for about five years now. I spent the first four years as an adult services librarian, and am now a children’s librarian and branch manager of the Ocean View location. I’m an avid reader of graphic novels, but not so much manga. However, I do try to stay on top of what’s popular.

Thomas: My name is Thomas, and I am a Teen Services Librarian. I’ve been a librarian for eleven years, and I have worked in public libraries for thirteen.

Manga existed in my library system before I arrived, but it had not been separated into its own collection. My first librarian position was at a branch location where I had the freedom to experiment with promoting the graphic novel collection. Since I could not add labels to the books, I considered what already made them stand apart. Our readers would often ask for the manga, and it was clear that being able to browse all of them at once would be a big help. There was also the convenience factor that most of the manga titles were paperbacks of the same or similar height, so they were easy to group together. People didn’t have to pick through the GN collection looking for manga because it was all in one spot! Manga circulation took off soon after, and the collection received its own label and shelves systemwide.

Currently, I work in a teen-specific area of the building that has a limited selection of manga so that browsers don’t have to go to the general manga collection in the adult area two floors up.

Ashley: I am a school librarian at the Samuel J. Tilden Educational Complex in Brooklyn, serving three high schools. I’m most well-known in the librarian community for my blog, Manga Librarian, wherein I provide collection development advice and cultural context pertaining to manga. I am also a Knowledge Quest blogger.

I have been a librarian since 2018. Before that, I was an English teacher. When I came into my library, it had been defunct for ten years. This is a common problem in NYC schools, despite Chancellor’s Regulations that require every school to have a library and every secondary school to have that library staffed by a school librarian. When I came in, there were no books. Zero. So I had to build my collection from scratch. As a lifelong manga reader, I just naturally picked up the manga. I started with what I considered essential series: Fruits Basket, Naruto, and Ouran High School Host Club. I also donated all of the manga that I owned to the library.

Rebecca: I’m the Web and Systems Librarian at the Borough of Manhattan Community College (which is part of CUNY), which means most of my work is actually with behind-the-scenes-type things that most library users may interact with but not really notice. But, all of the librarians in my library are encouraged to actively develop parts of the library’s collection, which is how I ended up building up a manga/graphic novel collection. I’ve also only ever worked in academic libraries which is probably different from most of the other people you may be speaking to. We only serve adult users, and specifically, Community College users are very diverse in many ways, more so than at other types of institutions, so we have to keep that in mind when buying books. On the personal side, I’ve been into manga and anime since the late 90s when I was a kid and I would have never thought I’d have been able to incorporate my interests into work like I’ve been able to. I’ve been a librarian for about 12 years, and I’ve been at my current library for just over 3.

Editor: Samantha Ferreira

Header Image Photographer: SN040288, used under license via DepositPhotos